It is midnight. The moon is dim, and hundreds of diminutive people—bearded, flat faced, and pale, with large blue eyes—are hard at work atop Fort Mountain in northern Georgia. They’re building a zigzagging wall of rocks from east to west. The wall is only a few feet tall, but they hope it will protect them from the Cherokee, so much taller and stronger than themselves.

All across Appalachia, there are tales of bands of these strange people (Yunwi Tsunsdi in Cherokee), living in the region’s many caves and coming out only at night, because daylight was too strong for their weak eyes. “They come near a house at night and the people inside hear them talking, but they must not go out, and in the morning they find their corn gathered or the field cleared as if a whole force of men had been at work,” wrote Lynn Lossiah, Cherokee author of The Secrets and Mysteries of the Cherokee Little People. “Always remember: Do not watch.”

For centuries, stories of these “moon-eyed” people have captivated—and creeped out—locals and visitors alike in Appalachia. According to some legends, they were present before the Cherokee came to the area, and driven out in a battle at Fort Mountain, waged by the Cherokee when the full moon was too bright for their opponents’ sensitive eyes.

“We are asked everyday about the legend,” says Emmanuel Stewart, park manager at Fort Mountain State Park. “It’s one reason why many people visit.”

According to rangers, archaeologists estimate the wall at Fort Mountain was built between 500 and 1500 , but no one knows who actually constructed it. For believers, what’s left of the mysterious wall is proof that the moon-eyed people did indeed exist.

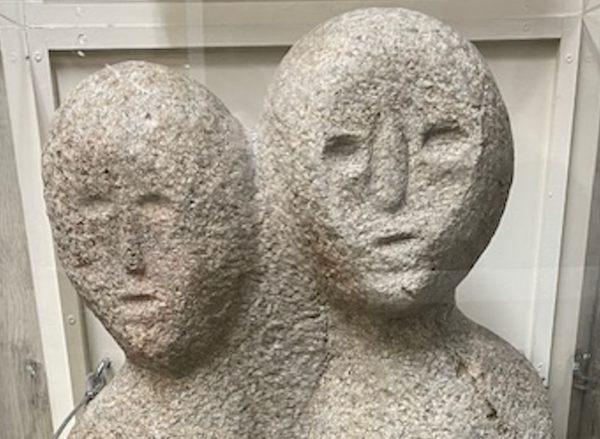

Sixty miles away, at the Cherokee County Historical Museum in Murphy, North Carolina, another object has been cited as evidence of their existence. The curious, three-foot-tall talc and soapstone statue was discovered by a farmer named Felix Ashley in the 1840s and features two entwined figures with oval heads and large, crescent-shaped eyes.

In 1882, an article in the Native American newspaper Cherokee Phoenix detailed the discovery of “three burying grounds” of extremely small-statured people—the longest skeleton was a mere 19 inches—near the Tennessee town of Sparta. Some of the individuals appeared to have adult teeth that were worn down with age. Several of the bodies, interred in stone coffins, were buried with items that may have been made from shells. There is no record of what happened to the remains, but the article is often mentioned by those who believe the moon-eyed people were real.

For most, however, “It’s just this old-timey Appalachia legend that people hear from their memaw,” says Brandon Schexnayder, who has explored the tales on his podcast Southern Gothic.

Schexnayder notes that the earliest preserved stories of the moon-eyed come not from Cherokee sources, but from white colonists. The 1797 book New Views of the Origin of the Tribes and Nations of America includes a mention of the Cherokee expelling the moon-eyed people, as does 1823’s The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee and James Mooney’s comprehensive Myths of the Cherokee, published in 1888.

“The legend of the moon-eyed people is not a major part of the Cherokee history and culture,” park manager Stewart confirms.

But white colonists were fascinated by the legend and speculated about who the moon-eyed people could have been. Some believed they were possibly descendants of a fabled community of albino people who were said to have lived in what is now Panama. Others adhered to the idea that the moon-eyed were actually descendants of the mythical 12th-century Welsh prince Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd, who allegedly landed in the Americas near what’s now Mobile, Alabama.

For example, in 1801 John Sevier, the first governor of Tennessee, related a tale of a war between the Cherokee and white people who had lived there before them, which he claimed was told to him by the great Cherokee leader Chief Oconostota. “At length the whites proposed to the Indians, that if they would exchange prisoners, and cease hostilities, they would leave the country, and never more return,” the chief reportedly said. Also part of the tale: A Cherokee elder named Pey possessed part of an old book from a descendent “of the Welsh tribe.” Sevier said that he had searched for the book but discovered it had been destroyed—conveniently—in a fire.

Tales of Madoc’s “Welsh Indians” had captured the imagination of jingoistic colonialists since Elizabethan times, because their purported existence meant that North America had been “claimed” for the English long before Columbus arrived in 1492. Thomas Jefferson was a firm believer in them and encouraged Lewis and Clark to search for them during their trek westward (they found none).

There were Welsh people living in Appalachia when the moon-eyed people stories began circulating, however. In the 18th century, Welsh settlers came to the region to mine its mineral-rich mountains, leading to tensions with the Cherokee, whose land they were plundering.

“They called the Welsh ‘moon-eyed people,’ not because they were small, white skinned, and the men bearded, but because they lived underground and could see well in the dark,” Peter Stevenson wrote in the 2019 book The Moon-Eyed People: Folk Tales from Welsh America.

While this version of the story may explain the Welsh connection to the legend, it’s at odds with the stories in Lossiah’s Secrets and Mysteries of the Cherokee Little People. Here, the moon-eyed people are not pale; they have the same complexion as the Cherokee. In Lossiah’s version, the “little people” can be hospitable or sneaky and treacherous, and they’re particularly vengeful when mocked or betrayed, traits that parallel European trickster elves and gnomes.

According to Lossiah, Cherokee tradition taught the importance of respecting the Yunwi Tsunsdi and their territory. “When a hunter finds anything in the woods, such as a knife or a trinket, he must say, ‘Little People, I want to take this,’” she wrote. “Because it may belong to them, and if he does not ask permission, they will throw stones at him as he goes home.”

Tales of the moon-eyed or little people of Appalachia persist to this day and, perhaps inevitably, “There are people saying [they are actually] extraterrestrials,” Schexnayder says.

While the true identity of the people that inspired the legend remains a mystery, “There is clear evidence that there were native peoples here before the Cherokee,” says Fort Mountain’s Stewart, citing the park’s ancient wall and other structures found in the region.

“But who this tribe was in the case of Fort Mountain, and whether they were the same [as the] moon-eyed people mentioned by the early settlers and their contacts is unclear,” Stewart says, adding that archaeological excavations along the wall have turned up few clues about its builders. “If the dwellings or homes could be found, then this would provide a huge breakthrough on their identity.”

Amid conflicting tales of mythical Welsh princes, lost tribes, and fairy-like forest creatures, there is one truth we know about the so-called “little people” of Appalachia, says Schexnayder: “The legend of the moon-eyed people shows that we don’t have to go that far back to know that we don’t know anything about where we live.”