Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we take a moment to look back at a decade(!!!) of The Lovecraft Reread/Reading the Weird, and ponder our pile of unearthed tomes.

Looking Back

Ruthanna: In 2014, “The Litany of Earth” had recently come out, and enough people had asked for a novel—including my eventual agent and editor—that I’d gone from “that’s just what people say when they like a story” to getting started on Winter Tide. I wanted to dive deeper into Lovecraft’s stories for material, but man, homework? How to make it fun and keep it going?

Well, accountability is good. Getting paid and getting an audience for my homework would be even better. Maybe a weekly column? But still, sounds like homework. How about with a collaborator? And this Anne Pillsworth person has also just published a Lovecraftian short on Tor.com…

If you’re ever nervous about a cold call, and who isn’t, learn from my example. I count reaching out to Anne as one of the best decisions of my authorial life. She was enthusiastically into it, and in the years since we have kept each other going through an increasingly wide-ranging project, opened each other’s eyes to new perspectives on old stories, and made each other laugh in the toughest weeks. (Or at least, I’ve had a few nights improved by a well-timed Kolchak intervention.) We’ve also enjoyed literary and Lovecraftian cons together and shared updates on families and gardens.

And Anne, who started reading Lovecraft in her teens, was a great complement to my deconstruction-first adult encounters, and kept me firmly grounded in the sheer coolness of this stuff. She’s also been consistently the first to push for expanding our remit to Lovecraft’s fellow weird dead, to living authors, to longreads, and even to movies on special occasions.

What I didn’t anticipate (aside from the idea that we’d still be doing this a decade later) was the awesomeness of the commenters. New suggestions, excellent insights, and metaphorical cookies for reading the really bad stuff. And often, a willingness to read along or pick up our recommendations—several authors have told us that they could see the post-related jump in their sales, which gives me a warm glow that is probably not a dangerously unstable ball of eldritch energy in my chest. I appreciate you all so much.

Onward! I’m eager to find out what new mind-bending discoveries await in the coming years!

Anne: Five hundred posts and counting into our exploration of weird fiction, poetry, and the occasional video! Oh, and one graphic novella interpretation of Blackwood’s “The Willows.” This feat must be equivalent to reading all the Mythos tomes in Miskatonic U’s dark archives, or at least the Necronomicon, cover to human-skin-bound cover. You’d think I’d have been driven mad, quite mad, by now. I assure you, albeit with palsied fingers on the keyboard, that I am quite sane. Never mind the low, maniacal giggling you may hear coming from my heavily curtained chamber. That’s just the dog, I mean, the parrot. Yeah, the parrot. Don’t ask me where he picked that up.

Discovering the Classics

Ruthanna: We started, as the original Lovecraft Reread title implied, with a focus on Lovecraft’s own stories. From there we started pulling in Long, Poe, Moore, and other authors who couldn’t complain about our opinions without necromantic intervention.

Among the Lovecrafts, it was the late stories with weird worldbuilding that most grabbed me—the ones that showed him wrestling with the appeal of the alien even as he continued to insist that questioning Anglo norms could undermine the very fabric of reality, and the ones that most invoked my own attraction-repulsion. Are elder things “men” because they have scientific curiosity or because they keep slaves—and what kind of people might shoggothim be in their own right? Are the Yith the universe’s best librarians or worst colonizers? Can we be cosmopolitan without giving up our ability to act? (Yes, duh, and could the Outer Ones please learn to attach those brain canisters to a nice Boston Robotics chassis?)

It feels… I can’t say weird, can I… it sure does feel a way to have used these as a safe way of getting insight into the bigoted mind, as that unpleasant understanding has become so much more relevant in the past decade. (What modern folk will be excused, in a century, as being “of their time”?) But Lovecraft was never so much saying the quiet part aloud as unaware that it was meant to be the quiet part. He was not only completely un-self-conscious about his prejudices and fears, but a good enough observer to pick up hints of the personhood of those he feared—and again, un-self-conscious enough to not think of effacing those hints. It’s what drew me into Innsmouth in the first place. Even his worst stuff—“Horror at Red Hook” and “Medusa’s Coil” and “The Mound”—has enough of that contrast to inspire flipside responses.

Among the other weird classics, the Chambers’s King in Yellow stories were a particularly delightful discovery. It’s a tiny set of work compared to Lovecraft, but rich enough to inspire a lot of follow-up—and viciously, beautifully satirical in a way I hadn’t expected.

Naming the Unnamable

Anne: I’ve been scrolling through the dark archives of the combined Lovecraft Reread and Reading the Weird posts. It’s crazy (strictly in the metaphorical sense) the range of weirdness Ruthanna and I have delved into. I was hoping to pick a list of favorites, but there’s no way; such a list would run to half or more of the pieces we’ve covered. Some of these are stories I’ve loved for a long time. More are stories, and authors, I discovered for the first time. Honestly, there were maybe half a dozen I disliked. Howard, I’m looking at “Sweet Ermengarde,” and yes, I know it’s just a toss-away parody. Still. How could you.

Instead of a list of favorite stories, I’ve picked out some favorites among the blog titles that Ruthanna has conjured over the years. A generous handful feature Lovecraft’s notoriously overused descriptive adjectives. For example (my italics):

Here’s a choice use of one of his Necronomicon quotes:

There’s also much sound advice for writers and other creatives:

Miscellaneous picks:

First and second runners-up are our two anime series:

And the winner is:

- I Ain’t Got No Body: Amos Tutuola’s “The Complete Gentleman” (See, the bad guy in the story is just this skull, hardly Complete, and no Gentleman, either. Get it? Never mind. It was an actual coffee-snorter for me.)

The Full, Twisted, Weird Family Tree

Ruthanna: The last decade has seen a flowering of weird fiction. While there’s all sorts of awesome stuff in the second half of the 20th century, there’s also a certain tendency to hew close to classic tropes and characters. But not only has the 21st seen a rise in deconstructing those classics, I also sense a surge in the original Weird goal of trying out new formats, developing new sources of WTF attraction-repulsion, and metaphoring the hell out of modern fears and alienations. The apocalypse is imminent, ever-shifting, and full of eyes watching you from unexpected angles—might as well get some good art out of all these eschatons.

No one will be surprised that I put Sonya Taaffe at the top of my list of modern masters—her gloriously lyrical language fleshes out everything from queer Jewish Deep Ones to new kinds of haunting. But I’ve also fallen for Nadia Bulkin, Livia Llewellyn, Amelia Gorman, John Langan, Ng Yi-Sheng, and so many others (not to mention expanded my love for McGuire/Grant, Elizabeth Bear, Max Gladstone, and Sarah Monette). I’ve gotten to appreciate the chapter-by-chapter brilliance of Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House and Jemisin’s The City We Became. I’ve gotten the most tongue-tingling tastes of the weird in translation, from Anders Fagers’s Swedish cults to Yan Ge’s sorrowful beasts to Borges’s Red House.

I’ve gotten completely incapable of answering “What weird authors do you recommend?” interview questions in under five minutes.

Defining the Undefinable

Anne: After cleaning up the coffee, I got all thoughtful, as one does in the aftermath of projectile merriment. One question had kept nagging me. It nagged so hard that I had to undertake what is for me a measure truly in extremis.

I composed a song parody. To the tune, no less, of Lionel Bart’s “Where is Love” from his musical Oliver!

Feel free to sing along, the more mournfully winsome your rendition the better.

Wha-a-a-a-at is weird?

Is it just the things we’ve feared?

Is it underneath a blasted heath

Or in dark cosmic leers?

Whe-er-er-er-ere’s the key

To stories that will harrow me?

Will I ever spot the exact plot

That gets weird to a tee?

Who knows where the weird abides?

Must I read both deep and wide

Til I can construe the answer to

What weird means to me, to you?

Wha-a-a-a-at, wha-a-a-a-at is weird?

As it seems every interviewee says these days, that’s a great fantastic very good question, [fill in interviewer’s name.] My cynical side interprets this as an attempt to flatter the interviewer while simultaneously stalling for time to think. What is weird, you the reader asks. I reply at once: That’s simply the most insightful question ever asked in the history of this or any other world, Reader! Meanwhile I’m feverishly consulting my trusty Merriam-Webster thesaurus. It defines weird in four ways:

- Bizarre; different from the ordinary in a way that causes curiosity or suspicion.

- Eerie; fearfully and mysteriously strange or fantastic.

- Magical; having seemingly supernatural qualities or powers.

- Unusual; noticeably different from what is generally found or experienced.

It’s interesting that the antonyms for all these definitions of weird are words like: normal, ordinary, commonplace, typical, conventional, familiar, regular, predictable, natural and unexceptional. Is Merriam-Webster implying that weird things are cool and intriguing, while nonweird things are blah and boring? Or am I just inferring that because I am myself a card-carrying weird sister? And don’t ask how you get a WEIRD card. If I told you, we’d both end up in the lightless pits of the nuzzling dholes, a destination on nobody’s bucket list. Nobody sane, anyhow, which I and you, Reader, obviously are, for we are lovers of the kind of stories this blog covers.

Bizarre, eerie, magical, unusual stories. By this generous definition, the weird would certainly include all the speculative genres. Or would it? Horror and fantasy, yes, but what about science fiction? Does SF squeak in as an Unusual, dealing as it does with technologies, societies, situations not yet known, normal, commonplace, but more or less possible as extrapolated from currently accepted science? Maybe not all SF should be considered weird. I’d put Andy Weir’s The Martian in the nonweird category. It’s so slice-of-life about what an astronaut left behind on Mars with certain resources and knowledge could do. It’s all sunlit rationalism to, for example, Octavia Butler’s darkly visceral “Bloodchild.” Yes, there could be a world where selected humans act as reproductive hosts to aliens. I suppose one could even describe that method of reproduction in so clinical a manner as to render it effectively (and affectively) “normal” in the context of the story. Butler doesn’t write that story. Nor does she make the arachnoid Tlic into monsters, their human egg-bearers into mere monster-fodder, thus producing a straightforward horror story. The first posited story would be “non-weird,” the second “weird” but simplistic. Instead Butler gives the relationship between humans and Tlic the social and emotional complexity to provoke chills that go beyond the “ick” factor into a much deeper experience of weirdness—a weirdness compounded of revulsion, dependency, coercion, and yes, even love in the time of parasitic breeding strategies, as Ruthanna put it.

According to the #2 and #3 criteria above, most of the stories we’ve discussed have been straightforward weird—they’ve featured pretty much all things eerie and magical, supernatural and unearthly, terrifying and astonishing, and (of course) eldritch and cyclopean. A few have been more subtle, relying on nuance and atmosphere. Shirley Jackson has been queen in this realm of the weird. The Haunting of Hill House, first in our series of longer form picks, is a masterpiece of all-out weirdness, bursting with paranormal goodness, but still allowing for some readerly doubt via Eleanor Vance, a narrator rendered potentially unreliable by her emotional instability and habit of fabulation. “The Witch” may feature a malevolent witch or just an overimaginative child and a sociopathic old man, “The Daemon Lover” a sort of incubus or just a man who decides to permanently “ghost” his girlfriend on the day they’re supposed to elope. There’s even less of the overtly supernatural in “The Summer People,” but the townspeople’s slow isolation of summer residents who stay too long is eerie and portentous beyond any “normal” friction between rurals and city folks.

We haven’t tackled Jackson’s last masterpiece We Have Always Lived in the Castle, but it could make the ultimate case study in how a novel that has no supernatural or magical elements, that could be classified as mainstream fiction or mystery or psychological suspense, is nevertheless chillingly weird—and also a triumph of the weird over the normal, however painfully won.

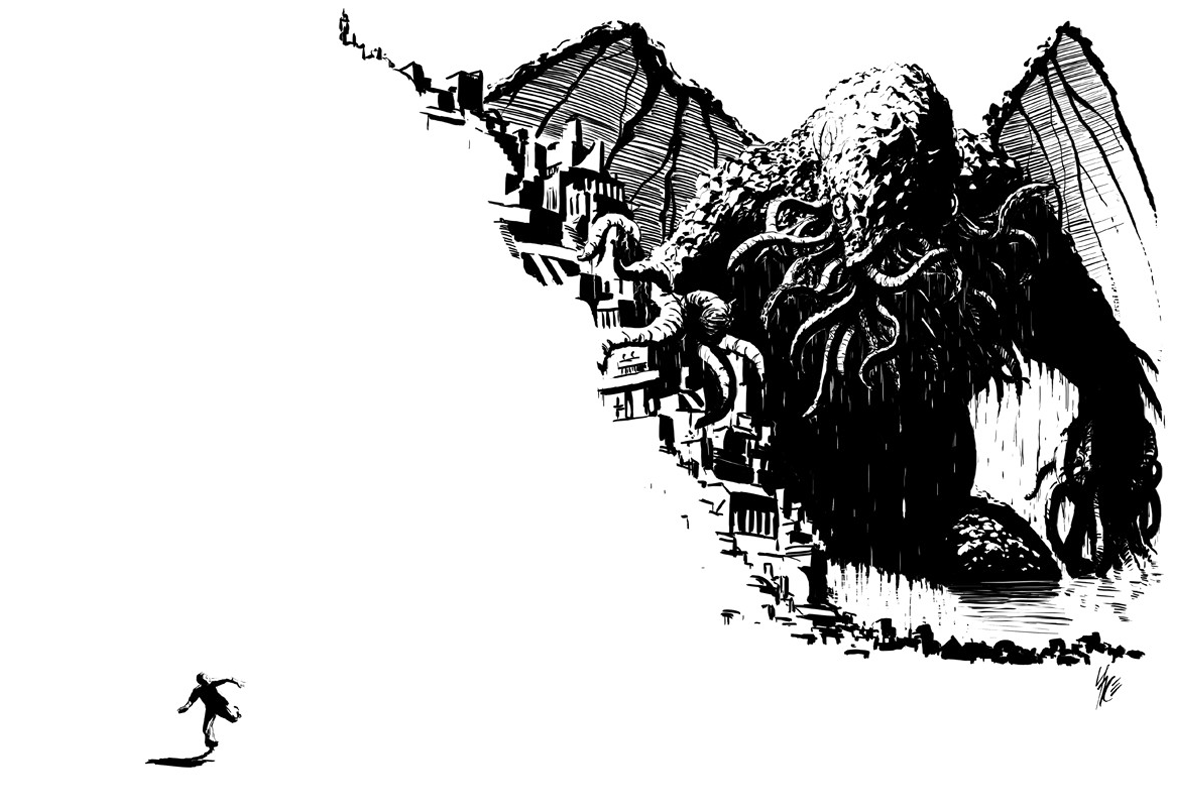

A triumph of the weird over the normal! Come to think, that’s a frequent theme in the stories we’ve read and a conclusion many of us can embrace. We, the weird, that is. It’s not all bad endings, the collapse of manors into tarns, the monsters unslain or even unslayable, the long-foretold return of the Old Ones…

To Infinity and Beyond

Anne: …although I’m not at all positive the return of the Old Ones would be a bad ending right now. That aside, long live the Weird and its Reading, and pints of Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar all around!

Ruthanna: So what’s next? Anne and I have always picked our reads by the seats of our pants and based on our current moods and star alignments, so the real answer is probably unpredictable. I’m excited to explore more work in translation, and speculative translation seems to be a growing area. There are several new weird and horror focused publication venues opening up, and I want to try out their offerings. The British Library has a whole series of themed Tales of the Weird collections out, full of intriguing selections, and the shelf of new anthologies is generally expanding far faster than I can keep up! The same goes for potential longreads, with abundant cosmic horror novels spilling into our little slice of reality every year.

My real prediction is that we will continue to sample, continue to squee and snark about what we find—and try not to stress too hard about our inability to get to everything. There are things man was not meant to know, and there are also more wonderful things to know than can fit into a human brain or a weekly blog column.

Next week, we finally return to our standard posting rhythm with Chapters 43-45 of Pet Sematary. Where were we again? Oh. Oh dear.