[ad_1]

The train that passes behind my apartment building twice an hour is always occupied by ghosts and monsters. It is occupied, too, by commuters, students, shoppers, and travelers bound for the tiny local airport—an airport similarly full of ghosts and monsters. The train is also frequently occupied by starry-eyed tourists, who take it to the end of the Yumigahama peninsula and disembark at the small seaside city of Sakaiminato, thrilled by the prospect of encountering—you guessed it—a hundred more ghosts and monsters. Sakaiminato was the hometown of one of the most beloved mangaka in Japanese history, Shigeru Mizuki, whose stories first ushered the supernatural creatures of Japanese folklore into pop culture in the 1960s. Since the 1990s, Sakaiminato’s main shopping street has been transformed into a gallery of yōkai character statues.

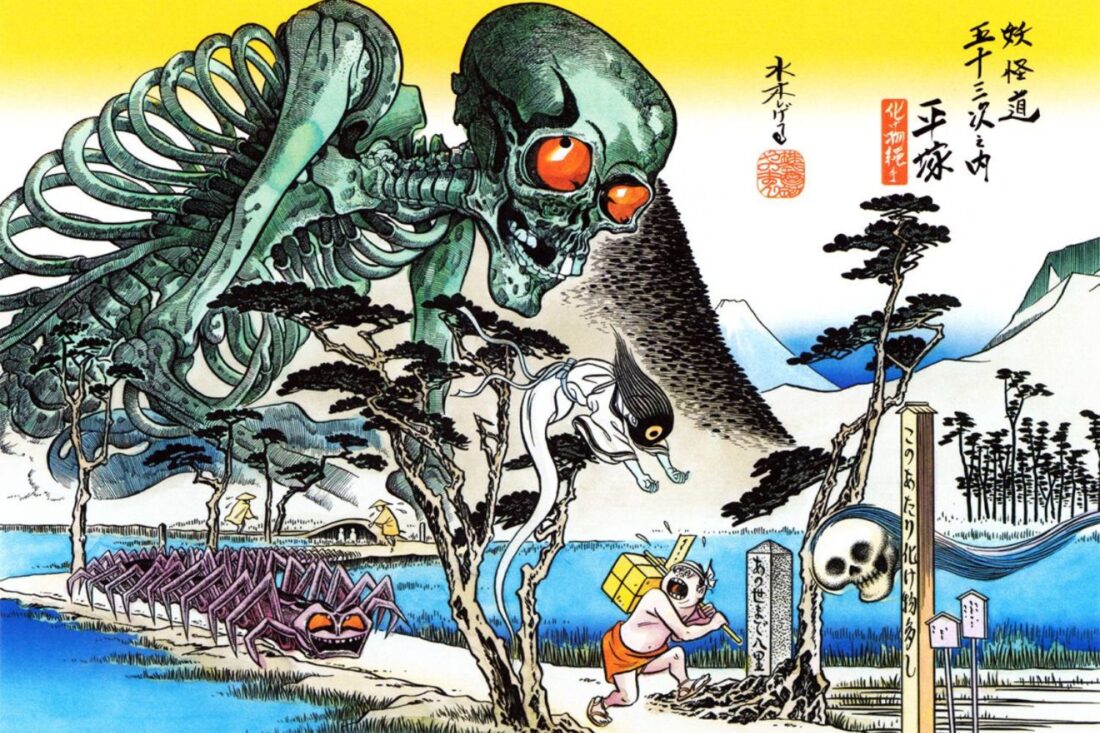

Given my deep-rooted adoration for all things yōkai, I have long been aware of Shigeru Mizuki. Still, it was not until I moved to Japan that I fully appreciated his cultural impact, which rivals that of Osamu Tezuka. In 2022, I booked tickets to a 100th-anniversary exhibition showcasing his work (Mizuki was born in 1922). An upper floor of a Ginza skyscraper was transformed into a yōkai menagerie, filled with Mizuki’s original illustrations and items from his home reference library. I reveled at not only Mizuki’s stylized, endearing, but often eerie illustrations of bath-tub licking spirits and bean-washing ghosts, but also the precious range of materials that had inspired himto create.

Among these cultural treasures was ukiyo-e artist Toriyama Sekien’s Gazu Hyakki Yagyō, or Night Parade of 100 Demons, which, at around 300 years old, is one of the earliest compilations of yōkai stories. While Sekien, an imaginative poet, made up some of the stories, many others originated from accounts of people in prefectures all across Japan. In the centuries since, the lines between invention and legend have blurred. Monsters survive best when they reflect the times, a fact Mizuki always understood. Following in Sekien’s footsteps, he blended yōkai stories and his own inventiveness to create his flagship manga, GeGeGe no Kitarō. In doing so, he gave an immortal home to stories and urban legends that had once existed primarily in the form of oral storytelling, and pioneered the entire supernatural manga genre to boot.

Mizuki Shigeru may not be so famous in every country, but the ripples of his writing have consistently defined not only manga and anime but speculative fiction as a whole since the Shōwa era. Big talk, perhaps, but true. Creators of some of the most internationally influential manga in the past few decades, including Urasawa Naoki of Pluto and Monster, Junji Ito of Uzumaki, Tite Kubo of Bleach, and Hiromu Arakawa of Fullmetal Alchemist, have cited Mizuki as an influence. Without Mizuki bringing yōkai into the zeitgeist, who knows whether ghost stories would have become such a staple in modern speculative fiction?

As profound as this impact was, Mizuki wasn’t content with redefining fiction alone. An unwilling participant drafted into the Second World War and veteran amputee, Mizuki was a staunch pacificist and vocally anti-nationalist later in life. He won two Eisners for his autobiographical non-fiction works, which refused to sugarcoat Japanese war crimes. Mizuki sought to educate Japanese youngsters in an era when the Japanese government was attempting to glorify the past rather than acknowledge the most shameful portions of the nation’s history.

After he died in 2015, many writers published wonderful tributes to Mizuki (I heartily recommend this piece by Zack Davisson at The Comics Journal). I initially hesitated to write about Mizuki because a man with such a profound legacy is hard to encapsulate in a little essay in an anime column.

But I have a specific angle: I live a few train stations from Mizuki’s old ’hood, out here in Tottori prefecture, and I am immersed in his legacy on a daily basis. The pride that people in the San’in Region take in their hometown hero is as well-placed as it is infectious.

So why not join me for a little stroll down a treasured local haunt, Mizuki Shigeru Road?

Welcome to Kitaro Road

The ghosts and monsters that adorn the JR West Kitaro trains along the Sakai Line are all characters from Mizuki’s most iconic manga. These include Kitaro, the one-eyed yōkai boy who defends human beings out of a sense of obligation rather than kindness; his father, Medama Oyaji (Eyeball Daddy), an undead repository for all things yōkai, who watches over his son and keeps the audience in the loop; Nezumi-Otoko, the lewd and cowardly rat yōkai Mizuki claimed to relate most to; Neko-Musume, the cat girl who rocks a bowl-cut that few could brave. Their faces are painted on the walls and ceilings of the train and sewn into the upholstery so riders can take selfies with Kitaro peeking over their shoulders. Throughout the journey, the cast of characters announces the stations and destination, bickering amongst themselves.

Along the way, every one of the sixteens stations has a yōkai nickname and mascot of sorts. At Goto station, for instance, those waiting for the train are loomed over by the image of dorotabō, a yōkai representing the vengeful ghosts of farmers whose carefully tilled fields have gone to seed after their passing. Fun! There aren’t any fields in this part of Yonago, but maybe there used to be. The most important station along the route is undoubtedly Yonago Airport. The little airport is home to numerous Kitaro tributes, including a ghostly whale suspended over the tiny food court and gorgeous stained glass windows featuring a collage of Mizuki’s artwork. And all of this before the train even reaches Mizuki’s hometown!

Though Mizuki was born in Osaka, he spent his childhood in Tottori. Though Sakaiminato has never been a large city, in the 1920s it must have felt smaller still. Mizuki admits to being good at punching as well as drawing; not a bully, but a kid who refused to be bullied. Perhaps it isn’t surprising that his most famous creation, Kitaro, is also a tough cookie. Emerging from his mother’s corpse after a wasting disease destroyed her, Kitaro is born into a grave and, depending on the anime adaptation in question, immediately loses one eye by cracking it against a gravestone. The sole survivor of the Ghost Tribe of humanoid yōkai, Kitaro is a spooky little kid by nature and just as scrappy as Mizuki himself. He kicks his geta at his enemies to devastating effect and uses his yōkai-magic imbued chanchanko (kimono vest) to bind them. Kitaro is only as heroic as he is weird, a kid who is perfectly content with being an outcast, living in his little hut in Aokigahara, the Sea of Trees, a real-life forest near Kawaguchiko that is sometimes called “the suicide forest” due to its tragic history.

It seems likely that many of the little side streets of Sakaiminato in 1922 weren’t so different than they are now, and it isn’t hard to imagine adolescent squabbles taking place by the bay. Sakaiminato is far past its prime but remains a prominent fishing port. After the Second World War and the destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, it was temporarily the primary fishing port for all of Western Japan. Today, you can hop on a ferry from Sakaiminato to China, Russia, or South Korea, although I have heard the trip is deeply miserable. Alternatively, you can climb aboard the Rainbow Jet ferry to visit the beautiful Oki islands of Shimane, where cows and horses roam seaside cliffs weirdly reminiscent of the coasts of Cornwall.

But many visitors to Saikaiminato are seeking yōkai, not ferries, and the town is read for them. Visitors are encouraged to buy stamp-collecting books at the tourist information center or the little souvenir shops. Businesses all along Kitaro Road take part in a yōkai stamp rally. It isn’t easy to kneel down on the sidewalk and perfectly nail inky silhouettes of creatures like kasa-obake (umbrella ghost) and futakuchi-onna (the two-mouthed woman), but it sure is fun to try and catch ’em all. Japan has a rich history of collecting seals and stamps that goes back way farther than Pokémon cards. At shrines and temples, visitors pay just 300 yen for a goshuin stamp, hand-drawn calligraphy and a seal unique to each sacred place. Doing this for yōkai feels right, another example of how seamlessly Mizuki’s world blends the modern and traditional.

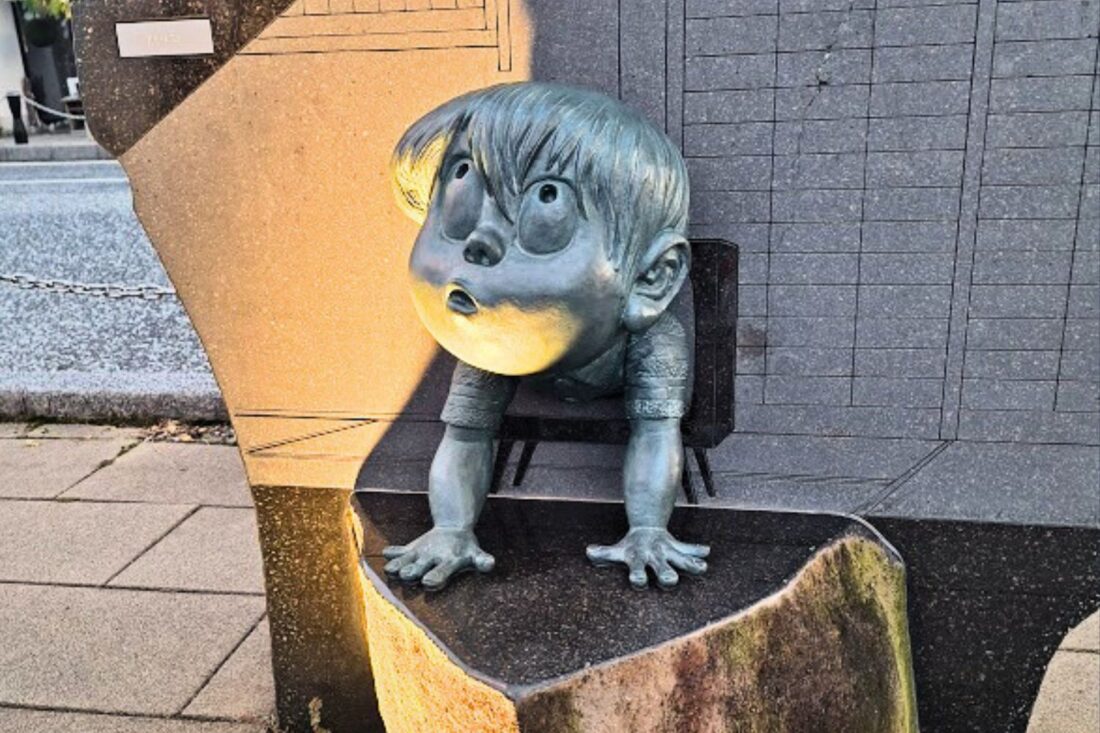

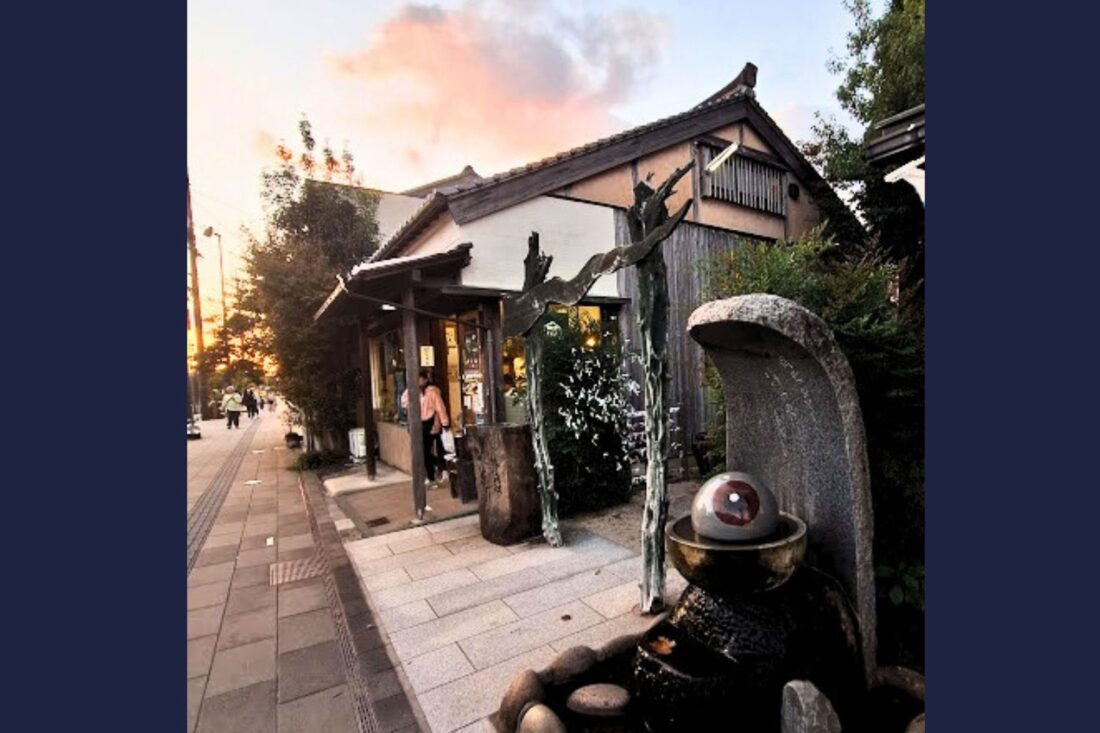

Perhaps as a nod to the Night Parade, in addition to yōkai-covered storefronts and a little park where visitors can bathe in a sake bowl alongside Medama Oyaji, Kitaro Road features 100 different bronze statues depicting Mizuki’s creatures. For every one of them that may be familiar to newcomers—tanuki and tengu and kappa, for instance—there’s another yōkai for fans in the know, unique to Mizuki’s canon. Take Terebii-Kun, a boy who climbs in and out of televisions (Could he have inspired Ringu?), or Kuchisake-onna, the slit-mouthed woman, who long existed as an urban legend, but was not declared a yōkai officially until Mizuki added her to one of his collections. Such was Mizuki’s power: he could elevate an idea to lore at his leisure.

At night, the bronze statues are illuminated by yellow streetlamps with bulbs modeled after Medama Oyaji, massive eyeballs keeping watch over the street. Yōkai silhouettes are projected onto the sidewalks. Mizuki Road felt especially magical when I stayed long after sunset during Minato Matsuri, an annual summer festival. Visitors donned yukata and children strapped Kitaro and Neko-Musume masks to their heads (and Pikachu too, for good measure). While fireworks lit up the darkness in the cicada-ridden heat, it did not feel impossible that a yōkai might be among the crowd, enjoying the spectacle. Summer festivals really do feel otherworldly, and I don’t care if that’s the dehydration talking.

Optimistic Monsters

“Just looking at him makes me want to cry,” my friend told me just last week, when we paused to admire a particularly endearing statue along Mizuki Road. It depicts Kitaro crouching on a stone, unaware that on a pillar above him his father, Medama-Oyaji, is watching over him.

“Why?” I ask, almost laughing.

“Because he just loves his son so much,” she says, with feeling. “It makes me want to cry; he’s so good.”

She’s right, though. Kitaro’s father, one of the last remaining members of the living yōkai Ghost Tribe, was wasting away due to disease, shriveling to a husk alongside his pregnant wife. But he could not bear the thought of his son growing up all alone. Rather than vanishing entirely when death claimed his body Medam Oyaji’s soul and mind transferred to his eyeball. In this way, he ensured that he could always take care of his son, even when his body had long become dust.

The backstory is gut-wrenching, when you take away Mizuki’s deceptively playful art. It would be easy to dismiss Gegege no Kitarō as simple children’s entertainment. Mizuki was a creator who experienced war all too intimately, along with all the cruelty and kindness it brings out in people. After American forces bombed his field hospital in Papua New Guinea, Mizuki lost his arm but found friendship with members of a local tribe of Tolai people. When he returned home to Japan, his brother was convicted for war crimes. Perhaps it was his brother’s shameful actions, as well as the collective horrors of the Second World War and his own country’s missteps that solidified Mizuki’s pacifism. He understood that people are flawed across the board, and loss is relative, but some truths and connections are vital no matter what form they take. In stories, maybe that looks like a dead dad transforming into a spectral eyeball to keep his boy safe. In life, it meant advocating for fellow amputees and writing accurate, objective portrayals of world history—controversy be damned.

If there were no depth of humanity to Kitaro, would people speak so highly of the series half a century after its first iteration? Would I still be taking pictures of my elementary school students dressed as Neko-Musume each Halloween? Would Sanrio be hawking collaborations with these characters in the 21st century? (Well, scratch that last one; Sanrio collabs with everything.)

Mizuki always kept his work grounded in the lives of everyday people. Famously, his first influence in childhood was his elderly nanny, NonNonBa, who told him yōkai stories he was way too young for—stories that helped spark his wonderful, lightly morbid imagination. She understood what Shigeru and his countless fans do, too: “spooky” and “fun” are good bedfellows, and the darkest stories of death and spirits help us appreciate life and daylight all the more.

Shigeru Mizuki, even after his death, gives the impression of having been one hell of a decent human being precisely because he did not deny his human flaws. He wasn’t a saint, and his characters are far from saints, too—they are strange and sometimes cruel and sometimes friendly and sometimes inappropriate and sometimes greedy and sometimes annoying. But… who isn’t?

Arguably, the most important human character in GeGeGe no Kitarō is Kitaro’s adoptive father. Sometimes he is depicted as monstrous himself, a resentful blood bank employee who only raises Kitaro because he is afraid of the boy. In the earliest iterations of the manga, Kitaro’s adoptive father holds little to no affection for the spooky kid that has become his burden. But as the years have progressed, the lens has softened on this frightened blood bank employee. In the 2023 film Birth of Kitarō: The Mystery of GeGeGe, he is more sympathetic and even fond of Kitaro and his parents. Mizuki passed away in 2015, before this adaptation came to be. But perhaps because he so encouraged empathy during his long life, the people of Japan have warmed toward monsters across the board…

And what did Mizuki name this supremely conflicted human character?

Mizuki. Of course.

The Road Goes On

One of my favorite statues along Kitaro Road does not feature yōkai, but Mizuki and his wife, Nunoe. The two are depicted as an older couple walking side by side. Their statue stands on a silver orb that reflects the river and city and people around it. Nunoe and Shigeru came together thanks to an arranged marriage, but their marriage was a strong one. Her own autobiography, Gegege no Nyōbō, was adapted into a television drama in 2010, and its popularity brought even more fans to Sakaiminato. Other favorite locations along the road are the yōkai shrine and a sake distillery that features Medama Oyaji on its bottles and signage. Every time I go to Kitaro Road, I notice something new, and small, and charming.

A 2023 article from The Asahi Shinbun commemorated 30 successful years since the establishment of Kitaro Road. Transforming the heart of town into a ghost haven was a desperate attempt to revive the long-dead shopping street. While some townsfolk protested the idea of ghosts occupying their town, Tomonori Kurome, the city official responsible for the proposal, got approval from the mayor. He approached Mizuki with trepidation, however, because it was unlikely the struggling city could afford to license Kitaro.

Shigeru Mizuki banished those fears in an instant. He said that he would not accept a cent from the people of Sakaiminato, and would permit them to use his characters and works however they saw fit. In the years after Mizuki Road was established, Mizuki himself visited when he could. Proudly displayed in some of the gift shops, amid the clutter of Nurikabe-shaped chopstick rests and Ittan-Momen towels, I have spotted photographs of Mizuki visiting those very shops, beaming alongside the Oba-sans and Oji-sans that ran them. Autographed Mizuki sketches hang over some of their cash registers. Pictures of him attending a parade in town are visible to window shoppers.

Just as Medama Oyaji watches over his son, Mizuki still watches over his hometown, and the people of Japan as well—and this country is so much the better for it.

I cannot stress enough how remarkable a man Mizuki Shigeru really was, and I recommend reading his works to get the full, firsthand experience of the world he created. Many are available in English courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly. Additionally, if you’re interested in yōkai, check out my recent essay on Natsume Yuujinchō or look into Tuttle Publishing’s catalogue of yōkai content. I’ll be visiting Toei Animation Park in December to see the yōkai parade, too, so more on that later!

Winter is approaching here, and there’s snow on the local volcano, but next up, I’ll probably be visiting the desert with a look at both Trigun (1998) and Trigun Stampede (2023). A piece on Metaphor: ReFantazio is also in the works… as soon as I can get deeper into the game. Oh, Atlus, you do make them long and weird!

Anyhow… what are you watching now? Thoughts on Mizuki? On other yōkai anime? Let me know in the comments!

Up Next:

- Trigun (Madhouse, 1998) Available via Amazon Prime and Hulu.

- Trigun Stampede (Studio Orange, 2023) Available via Amazon Prime and Hulu.

[ad_2]

Source link