In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

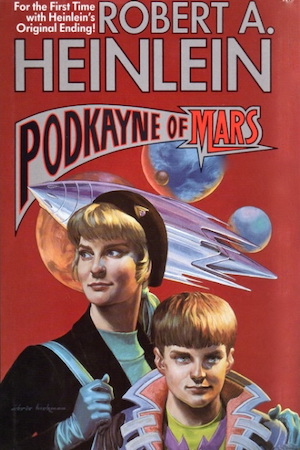

Podkayne of Mars is far from Robert Heinlein’s worst book, but it is definitely one of his less successful efforts. The tale reads like one of his juveniles—albeit one with a rare female protagonist—but Heinlein grafts on a moral targeted squarely at adults. Then there’s the fact that Heinlein’s original ending was disliked by the editors to whom he was pitching the story. The result of all this dissonance is a tale that has some entertaining parts, but ends up being a mishmash of disparate elements.

Heinlein had originally intended the book as kind of a travelogue, following a young girl in her travels around the solar system, and he created one of his most appealing characters in young Podkayne Fries. Perhaps if he had stuck with his original vision, he would have produced a charming, feminine counterpart to the popular juvenile series he had written for boys. On the other hand, some elements of the future society he’s depicting simply don’t work—while his settings often felt real and lived-in, his portrayal of life on a space liner in this book feels downright reactionary, and the future he envisions reflects attitudes, especially regarding women’s roles, which were already changing when the story was being written.

After much of the book was completed, Heinlein grafted on elements that changed the entire tone of the work. When his editors asked for changes, the normally astute Heinlein seemed baffled by their resistance to his artistic vision. Ultimately, the problems with this novel went far deeper than the relatively minor changes he made in order to satisfy their criticism.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) was one of America’s most celebrated science fiction authors, frequently referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Glory Road. From 1947 to 1958, he also wrote a series of a dozen juvenile novels for Charles Scribner’s Sons, a firm interested in publishing science fiction novels targeted at young boys. These novels include a wide variety of tales, and contain some of Heinlein’s best work (you can follow the links to my reviews of each title): Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Spacesuit Will Travel.

Podkayne of Mars

Podkayne Fries is a child of privilege on a newly independent Mars, a young woman on the cusp of adulthood, who dreams of someday being a spaceship captain. Her father, a noted historian, lost an arm in the struggle for independence, and her great-uncle Tom, a Senator-at-Large in the Martian government, was another hero of the rebellion. Her mother is a prominent engineer who oversaw the transformation of Mars’ moons, Deimos and Phobos, into commercial spaceports. The one dim spot in Poddy’s life is her irritating younger brother, Clark, who is smarter than her and just about everyone around him, and is dedicated to using that brainpower to make Poddy miserable.

The book takes the form of first-person entries from Poddy’s diary, although there are also occasional entries Clark has made in invisible ink—her diary is not as private as she thinks, and he delights in leaving his mark in it. Heinlein has a breezy prose style that makes the book flow smoothly, although occasionally some of Poddy’s observations feel less like a young woman’s reflections and more like something an older man might think…

Poddy has dreamed of visiting Earth all her life, but just as the whole family is ready to leave on a trip to the homeworld, disaster strikes. Mars has a eugenics program, and as members of the planetary elite, her parents are obligated to have five children. The youngest three were frozen, to be decanted and raised at a time convenient to the family, but an administrative error has resulted in their untimely birth, and now her parents have their hands full with three new babies and are unable to travel. But good old Uncle Tom not only agrees to take Poddy and Clark on their trip, but he convinces the Marsopolis Creche to pay for the voyage as reparations for their mistake, and they get a berth on a liner going to Venus on its way to Earth (two planets instead of just one!). They happily depart, although Poddy finds her luggage three kilos heavier than she thought, and Clark pitches a fit at customs that causes him to go through an invasive search. Uncle Tom’s political status allows him and Poddy to breeze through without a second glance, and Clark eventually joins them. The liner they are boarding, Tricorn, is a modern ship that voyages at constant boost, even better than the one they were originally scheduled to ride.

While Heinlein’s predictive abilities result in some convincing aspects of Mars society (he even has a character using a portable pocket telephone at one point), he fails in some important ways. His society is still thoroughly rooted in the 1950s. It is male-dominated, with Poddy’s mother being a rare exception to the status quo. And the customs and service aboard the liner are the same as one would find aboard an Earth-bound ocean liner in the days before passenger airplanes made that mode of travel obsolete. There are formal dinners and dances, and a very stratified society divided by passenger classes. Poddy charms her way into nearly unlimited access to the control room, but finds to her dismay that astrogation involves lots of tough math, and command decisions can be very stressful. She meets “Girdie,” a newly divorced socialite who is returning to Earth. Poddy is also befriended by a matronly old woman, who starts treating her like a servant, and accuses Poddy of putting on airs when she stands up for herself. Poddy then overhears the woman gossiping about Poddy’s mixed heritage, and we find Uncle Tom’s side of the family is of Māori descent (Heinlein might have thought naming a person of color “Uncle Tom” was funny, but I didn’t).

Poddy discovers that Clark hid an object in her luggage that he was paid to smuggle aboard the ship—a miniature nuclear device. Clark assures her he disarmed the bomb, but is hanging on to it in case he needs it (!?!). And here we begin to see Clark portrayed as not just an irritating little brother, but a flat-out sociopath. There is a solar storm that requires everyone aboard Tricorn to take shelter in the center of the ship, where Poddy and Girdie are pressed into service to help take care of infants. Poddy realizes she enjoys taking care of babies, perhaps more than she might enjoy being a spaceship officer.

When they reach Venus, they find a hyper-commercialized culture where everything is a commodity. It turns out that Girdie’s ex-husband had lost all her money, and she has decided Venus is the best place for her to regain a fortune, so she takes a job in one of the casinos. Uncle Tom spends a lot of time with the Chairman of Venus while Poddy is wined and dined by the Chairman’s son. But then Clark is kidnapped, and it turns out Uncle Tom’s vacation with the kids is really a cover for a secret diplomatic mission. Poddy finds clues to where Clark might be and follows them, but finds herself captured as well, only to discover that Uncle Tom is also a captive. The woman behind the plot, someone they barely noticed on their voyage, lets Tom go, keeping Poddy and Clark as leverage to ensure Tom’s compliance in undermining his upcoming political negotiations. Poddy is threatened with being put in a cage with a brutal Venusian creature, and is harassed by a tiny, semi-intelligent Venusian “fairy.” But Clark kills the woman, arms his nuclear weapon on a timer to destroy her safe house (how he managed to hide that weapon during his capture is left as an exercise for the reader), and he and Poddy head out separately toward safety.

Dueling Endings (Spoilers Ahead)

When Podkayne of Mars was originally published, it ended with a postlude revealing that while Clark escaped the nuclear blast that destroyed the safe house, Podkayne had circled back to rescue the Venusian fairy in the house, and was in critical condition. Her Uncle Tom calls Poddy’s mother and blames her for her daughter’s misfortune, insisting it was her lack of maternal parenting that had led to the incident. But with the 1989 publication of a posthumous collection of Heinlein’s letters, Grumbles from the Grave, the world learned that the published postlude had replaced the version where Poddy died, an ending Heinlein preferred.

While I was preparing this review, the Heinlein Society serendipitously posted on Facebook an excerpt from William H. Patterson Jr’s two-volume biography, Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, which discussed the controversy over the ending of Podkayne of Mars. It revealed that Heinlein did not consider the book a juvenile, and also that he considered its main message that women should devote themselves to raising their children rather than trying to pursue a career. That can be seen in Podkayne’s growing realization that she preferred caring for infants over navigating a spaceship. Clark’s maladjustment and lack of empathy was also meant as an indictment of his mother’s decision to pursue a career—he’s a living example of the risks of ignoring a child, with only the trauma of losing his sister being able to penetrate his selfish worldview.

When Jim Baen obtained the rights to a number of Heinlein books in the early 1990s, he decided to generate some attention for his 1993 reprint of Podkayne of Mars by releasing a trade paperback version with both endings and holding an essay contest to see which readers preferred. And he was stunned not only at the volume of responses, but by the passion of the essays.

Not having a copy of Podkayne of Mars on my shelves, I bought that trade paperback when it was published. Seeing the contest, I suggested to my then-15-year-old son, Alan Junior, that we both read the book and prepare an essay. He agreed, and it turned out our votes cancelled each other out. With his Gen X practicality, he pointed out Heinlein’s original ending was the only one that logically flowed from the rest of the book, as it was improbable for Poddy to have survived the nuclear blast. I myself, being a bit more romantic, argued it was unfair for Heinlein to have written what appeared to be a juvenile, luring readers into empathizing with Poddy, only to kill her off as an object lesson for her brother, grafting a moral for adults onto a book for youngsters. Both of our essays were among those printed in the mass market paperback edition in 1995. Overall, the majority of essays supported future editions of the book appearing with Heinlein’s preferred ending.

It was a few years later that I found a term that put my misgivings about Podkayne of Mars into focus, and that term was “fridging.” Coined by Gail Simone in 1999, most of you will be very familiar with the “women in refrigerators” trope, in which violence towards female characters is used as a plot device to motivate the actions and emotional responses of male characters. That term certainly fits Heinlein’s original vision for Podkayne of Mars to a T. He had no problem sacrificing the viewpoint character of his book as an object lesson for her younger brother. And I have a feeling, had Baen’s contest and the debate about the ending been held after the critical discussion over fridging had permeated popular culture, popular opinion might have taken a different direction.

Final Thoughts

I remembered Podkayne of Mars fondly from my youth, largely because Poddy was such an appealing character, although I disliked the gloomy ending with her suffering grievous injuries (it was only later I found out how much more gloomy that ending could have been). Re-reading it for the Baen contest, I primarily focused on the ending, and the pros and cons of changing it. But reading the book again for this column, I found myself disliking it throughout. The “women belong in the home” theme was already becoming dated when Heinlein wrote the book, and now I find it downright offensive. I began to imagine what I would have recommended as changes, edits which would have started long before the ending. I would have suggested that Heinlein go back to stressing the same virtues of bravery, determination, and character that made his earlier juveniles so successful. I would have urged him to drop the “secret nuke” sub-plot, which painted Clark as so antisocial and arrogant he was more a prop than a realistic character. The theme of character growth could have been shown by Poddy and Clark learning to work together and respect each other during their escape on Venus, and by giving them the opportunity to see the world that exists outside their privileged bubble during their struggles in the wilds and among poor settlers. I definitely would have urged Heinlein to drop his insistence on shoehorning a cautionary tale about childrearing into a coming-of-age adventure story, a choice I think was tone-deaf at best.

And now that you’ve heard my opinions on the book, I turn the floor over to you. What are your thoughts on Podkayne of Mars? If you were Heinlein’s editor, reading it for the first time, would you have accepted his work without revision—and if not, what changes would you have suggested? And since Heinlein failed in his attempt to write a juvenile science fiction adventure with a female protagonist, can you recommend books that have done that successfully?