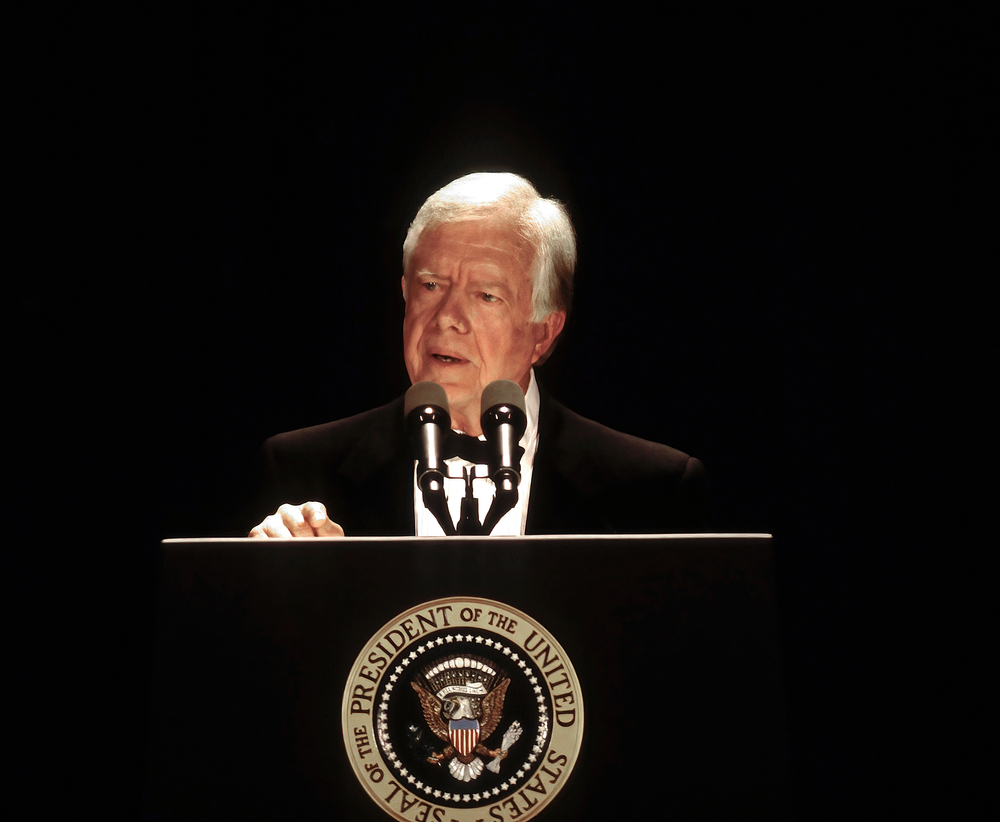

With Jimmy Carter’s passing, many will reflect on his impact at home and abroad. Yet, one his most personal acts will also stand as one of his most enduring legacies.

At 100, not only was our 39th president the longest-lived president, he was also to first to publicly elect hospice care, prioritizing the quality of his last days over simply being alive.

When he first enrolled two years ago, the family’s announcement was brief: Following a “series of short hospital stays,” the president opted to spend his remaining time in his home of 60 years, receiving hospice—medical care that supports patients and their loved ones holistically, focusing on what’s personally important. For Carter, that meant no more trips to the hospital.

One year into hospice, his grandson, Jason, observed that, “we have no expectations for his body, but we know that his spirit is as strong as ever.”

The physical changes were apparent the last time most Americans saw President Carter at the funeral of his wife, Rosalynn. The image of our former president seated in a wheelchair, his face thin and body worn, reverberated throughout the country, moving Americans to ask questions about what is meaningful to them as they face future healthcare decisions.

Hospice care is about living one’s life, on one’s own terms, just like former President Carter did. Although Carter’s family shared few specifics, they vocally supported his decision to focus on quality over quantity of life. Rather than release medical data, such as lab results, the family opted to share the simple pleasures that make even a former president human, like enjoying a scoop of ice cream.

President Carter’s end-of-life journey was the exception, not the rule. While 90 percent of seniors prefer to pass away at home, only 34 percent do. The other two-thirds die in a healthcare facility, often a hospital. This end-of-life acute care not only fails to honor patients’ wishes; it also frequently leads to avoidable patient harm, including infections, confusion, and falls. In-hospital care paradoxically leads to more pain and suffering and helps explain why we spend more on healthcare in the final months of life than any other country.

As physicians, we know there is a better way. Harvard researchers found physicians are significantly less likely than others to die in hospital, presumably because we’ve seen firsthand how aggressive end-of-life interventions often cause more harm than good.

Yet, as human beings, our usual drive is to stay alive. So, how and when do we choose, like President Carter, which path is best as we approach the end of life?

For healthy people, contemplating one’s mortality can seem unfathomable; for patients with serious illness, it’s commonplace. Patients want providers to talk with them about options for future care—including palliative care—specialized medical care focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of serious illness. Basic medical training doesn’t equip providers with the skills to effectively meet a patient’s values and goals with a holistic, personalized care plan. Palliative medicine specialists gain this expertise by completing additional training in optimizing the quality of life and complex medical decision-making. Our already strained healthcare workforce barely has a quarter of the palliative specialists needed for our aging US population.

Given that capacity constraint, we’ve been studying whether primary care providers (PCPs) could help fill that gap. The U.S. has approximately 200,000 of them, and most seniors have a dedicated PCP. PCPs don’t always have the expertise or resources to provide holistic care to all seniors who would benefit. To help PCPs better care for their sickest patients, we provided PCPs with essential elements of palliative training, including how to: identify patients who would benefit, discuss goals of care, and collaborate with specialized home-based care teams.

Studying nearly 2,000 seniors who died, we found that patients cared for by PCPs who collaborated with palliative care teams spent five more days at home in their final months and were two-thirds less likely to die in a hospital. In addition, their out-of-pocket healthcare expenses—a major source of hardship—were one-third lower.

Given the long-standing patient relationships that are at the heart of primary care, integrating palliative care is a natural extension of primary care—literally meeting patients where they are, including at home.

Importantly, palliative care is not “less” care, and many recipients actually live longer. Seniors receiving palliative care often continue to pursue life-prolonging treatments, such as chemotherapy and surgery, while ongoing support from an interdisciplinary palliative team addresses unmet needs, like spiritual care and pain management. The team is also available to guide patients considering focusing exclusively on symptom management and comfort, like President Carter did.

Reflecting on President Carter’s journey, and on the patients we studied who spent more and higher-quality time at home, our conviction has never been stronger⎯investing in the collaboration between primary care and specialty palliative care for the country’s seniors must be a national priority.

Ben Kornitzer is a physician executive. Nathan Goldstein is a palliative medicine physician.