In the gift shop of South Carolina’s Congaree National Park, visitors can choose between two maps to help them explore the largest expanse of old-growth bottomland hardwood forest left in North America.

In the first one, printed by the National Park Service, most of the detail is concentrated in the top left corner near the park’s headquarters: loops of hiking trails plotted in dotted lines, major waterways rendered in icy blue. The rest of the map—the park’s 22,000-acre backcountry—is depicted as a barren expanse of pale green, interrupted only by an occasional swirl of topography or the faint squiggle of a creek.

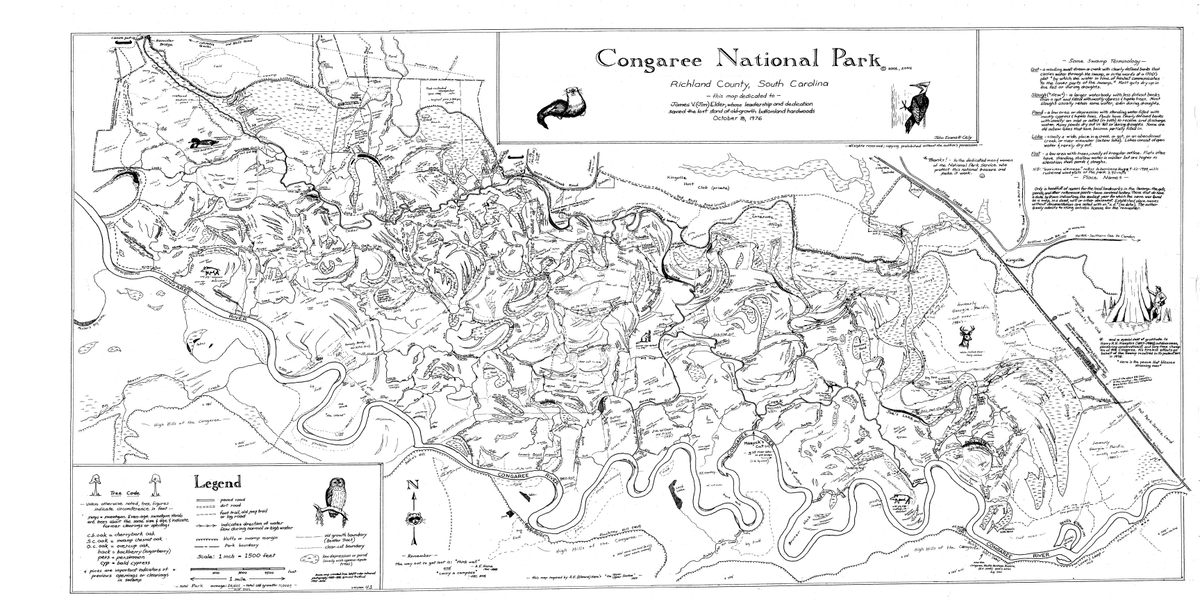

The second map, on the other hand, is a riot of detail. Drawn in fine, felt-tipped black, the same amorphous outline of the park’s boundaries bursts with embellishments: archaeological remnants, hurricane blowdowns, decades-old logging scars, decrepit hunting lodges, even soil damage from beavers and wild boars. Flagged are several of the park’s 25 “Champion Trees”—each representing the largest of their species in the country—and more than a hundred of the meandering, tiny channels that fill with tannin-dark water when the Congaree River rises and floods the forest each spring.

While the second map may look more like a whimsical illustration from a children’s book than a navigational aid, recent geological surveys have found it to be surprisingly accurate. It’s so precise that Congaree’s park rangers prefer it over the official version.

The Cely Map, as it’s known, is the creation of John Cely, a 77-year-old retired biologist who’s been wandering around the tupelo sloughs, loblolly stands, and sandy hummocks of the South Carolina swamp for almost 60 years, long before it was a national park.

Cely was 17 the first time he visited, a sophomore at Clemson University majoring in biology. He had written an admiring letter to the journalist Harry Hampton—who had been advocating for the preservation of the floodplain forest in his newspaper columns since the 1950s—and Hampton invited him to come see it for himself in 1967. Cely, who would go on to make his career as a bird biologist working for the state, was gobsmacked by the myriad wildlife and majestic woods he found there.

“That was a game changer,” Cely says with a throaty Southern drawl. “I’ve been in love with the place ever since.”

Over the decades, Cely has participated in the grassroots efforts that succeeded in safeguarding the land from development, first as Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976, and then as Congaree National Park in 2003. He also played a leading role in finding, measuring, and cataloguing the park’s Champion Trees, the largest concentration of the behemoths anywhere in the United States. He’s led wildlife surveys, bird-banding stations, and, for the last 20 years, a twice-monthly guided walk for visitors, introducing them to the flora and fauna of the swamp, located 25 miles southeast of the state capital of Columbia.

But in the late 1990s, Cely started to feel like he hadn’t done enough to contribute to the landscape he loved so much. “I didn’t have much to justify all these years of knocking around this place except for photographs and old memories,” he says.

One day, it hit him. “We needed a good map of the Congaree.”

It’s not that maps didn’t exist; it’s just that they weren’t very helpful.

“The problem with floodplains is that they don’t have any elevation, any relief, any real landmarks,” Cely says. “Everything looks the same.”

The existing maps, based on topographical surveys and aerial photographs, tended to flatten the place into a featureless void. A homemade, hand-drawn map, on the other hand, could depict all of the unique characteristics—the clear cuts, logging roads, and beech groves—that made its many acres navigable.

And in the Congaree backcountry, navigation can be a challenge.

“It can be a very dangerous and confusing place,” says John Grego, president of the Friends of Congaree Swamp, a nonprofit that supports conservation efforts in and around the park. Deep in the woods during high summer, he explains, both sky and horizon disappear completely in a jumble of tree branches and laurel thickets. “It’s very easy to get lost, to step off the trail and head in the wrong direction.”

When visitors did get lost, rangers had a hard time coordinating search efforts, given that so much of the swamp’s terrain was unmapped and unnamed.

To begin his project, Cely, who has no formal art training, created a base map of the park’s boundaries by tracing an aerial photograph. “Then I went to work filling in as much detail as I could,” he says. “A lot of the information was in my head. I just needed to put it to paper.”

For the rest, he hit the trail, “hiking and camping all over the place.”

This was 25 years ago, a time when GPS wasn’t yet widely available. So Cely relied on his compass and pacing to devise an accurate representation of the terrain, counting his steps to figure out how far to place, say, the stand of dead pines from the small oxbow lake on the far southeastern edge of the park. For days on end, he followed and sketched the hundreds of threadlike waterways that weave through the cypress, tupelo, and tulip poplars of the swamp, naming them as he did: Scrubby Gut, Horseshoe Pond, Big Snake Slough.

Cely was well aware that the Congaree people that inhabited the swamp for centuries before Europeans showed up likely had their own names for these places. “But so many of them have been lost to history,” he laments. “So I just used my imagination and did my best.”

All told, it took Cely about three years—or “a good long while,” as he puts it—to create his 4-x-2-foot map. When he showed his work to park staff in 2001, they reacted enthusiastically, placing it on sale in the gift shop next to the official map, with proceeds going to support the Friends of Congaree Swamp.

“I thought if I sold 50 maps, I’d be happy,” Cely says. Instead, sales are well into the thousands.

Perhaps more surprising to Cely, the map quickly became a critical tool for those tasked with taking care of the park and its visitors. “The best compliment is that rangers and law enforcement use it,” he says.

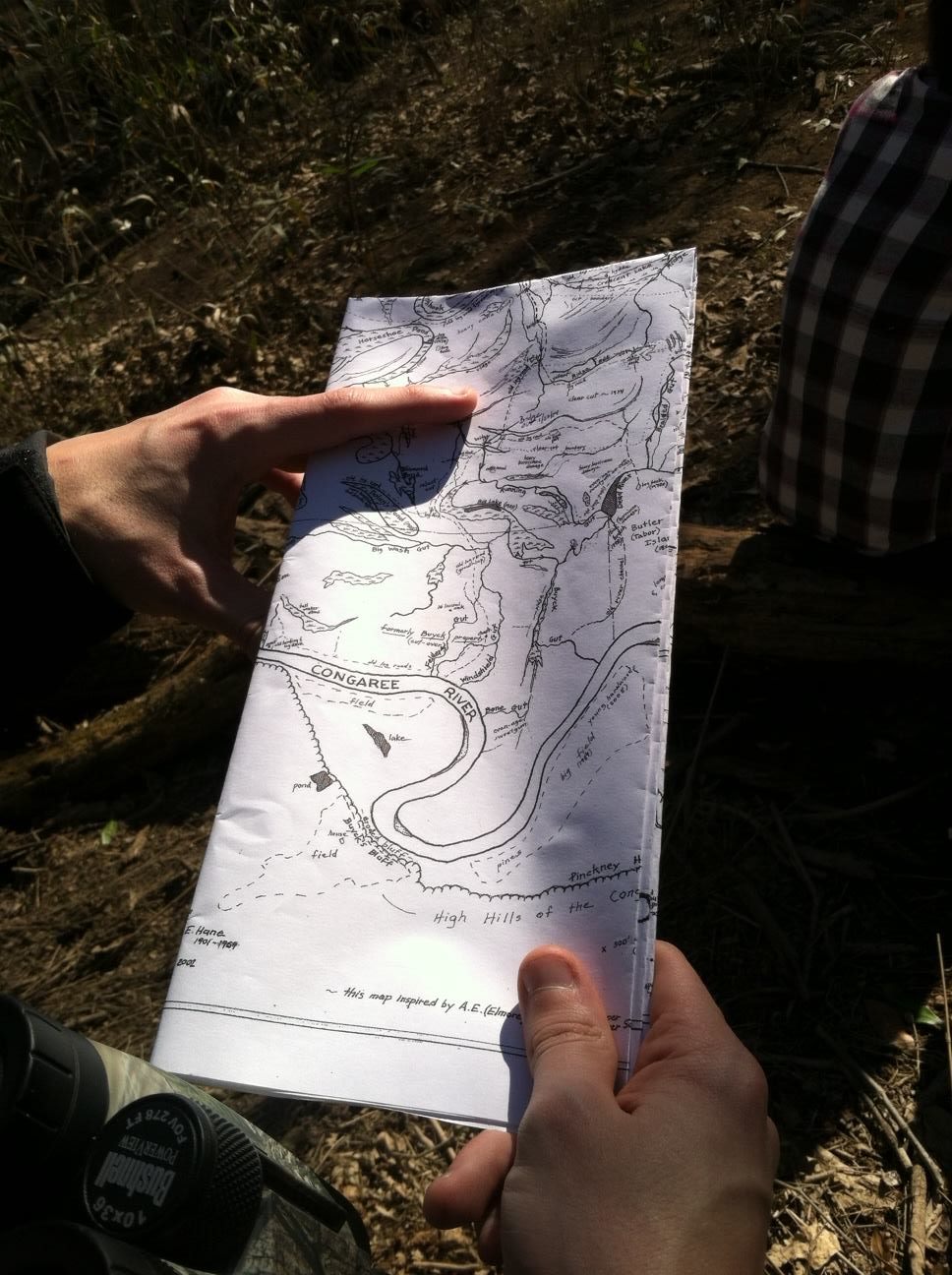

Grego cuts his map into small, pocket-sized sections to guide his weekly hikes. “Without John’s map, you’re kind of just stumbling around,” he says. “It’s remarkably accurate.”

So accurate, in fact, that a recent lidar survey found that the depictions of features in Cely’s map are largely precise to within eight meters (about 26 feet). “It is a remarkable achievement,” writes Raymond Torres, a University of South Carolina geologist who worked on the project. “The level of detail … and the accurate placement of that information is altogether astounding, especially given that much of the map was made prior to the availability of affordable GPS devices.”

Cely says he was pleased to have his work ground-truthed: “Things fit where they were supposed to fit.”

The retired biologist updates his map (currently on version 4.1) every now and then, after a hurricane passes through or a big tree falls—changes he’s apt to notice on his near-daily rambles around the swamp.

More than half a century after he first arrived, the park’s unofficial cartographer says that Congaree still contains mysteries, even for him.

“As many times as I’ve been down there,” Cely marvels, “I still find something new every time I go.”