NOTE: Spoilers for Ex Machina, Apartment 7A, and Severance (including the season two finale).

“I have to write about Defiant Jazz,” I told my boyfriend one afternoon while we were sitting on the couch talking about Severance. It was not the first time I had brought up this subject. Initially, I was uncertain as to what I wanted to write—what it was I needed to say about the bizarre alchemy of innocence and surrealism that imbues this particular dance sequence, a scene that manages to subvert all expectation for what a “drama” should be. To start with, I have zero rhythm. None whatsoever. I can barely tap my foot to a beat and whenever I try even a basic box step, my sense of left and right immediately betray me. I am not the person you’d expect to tackle this subject, but every time I thought about simply letting it go—I couldn’t. Defiant Jazz had lodged itself in my brain like a multisensory earworm. I could watch all four minutes and twenty-four seconds of it once a day, every day, for the rest of my life and still remain positively fascinated.

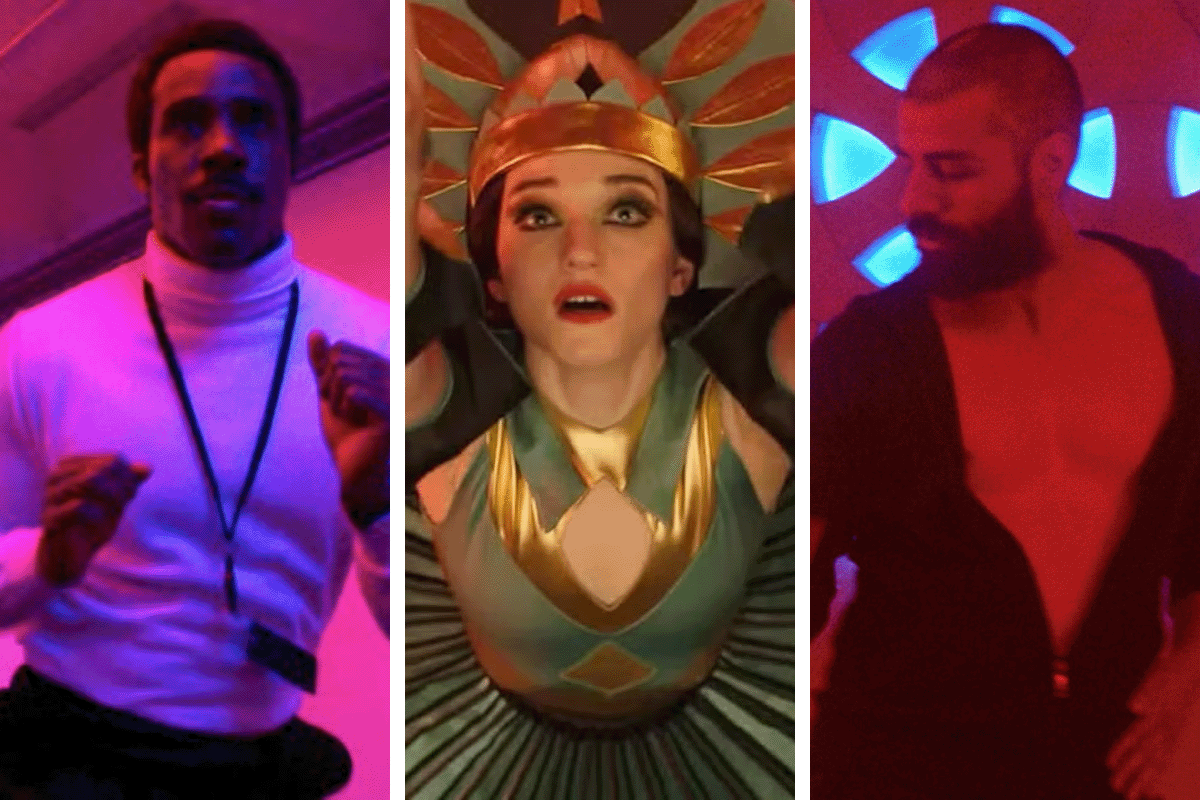

For context, “Defiant Jazz” is the title of season one, episode seven of the hit sci-fi series Severance, which debuted on AppleTV+ in 2022. In the scene for which the episode is so evocatively named, a member of the Macrodata Refinement Department named Helly R. (Britt Lower) has met her workplace goal. She is thus rewarded with something called a “musical dance experience” or MDE. Everyone in this department is severed, which means that a chip in their brains completely separates their works selves (known as “innies”) from their daily life selves (referred to as “outies”). As an innie, Helly presumably knows little to nothing about music. When Mr. Milchick (Tramell Tillman), the department’s supervisor and the only person in the room who is not severed, asks her to pick a musical selection, Helly chooses “Defiant Jazz” off a longer list of entertaining options (beginning with “Bawdy Funk” and ending with “Wistful Pipes”). What ensues is a wildly bizarre experience that temporarily transforms the clinical office space into something more alien, with Mr. Milchick grooving around the room and most of the severed workers awkwardly attempting to do the same, but hampered by diffidence, or perhaps reluctance. It’s increasingly strange and the viewer finds it impossible to look away as a sense of growing chaos and dread and color flood the screen.

If you’ve watched Severance, you know that this sequence ends with Dylan G. (Zach Cherry) leaping out of his chair, throwing Mr. Milchick to the ground, and biting him. Dylan has recently came face-to-face with his outie’s child, and the thought of having a family and children he didn’t know existed has been eating away at him throughout the episode, building up to this outburst. It’s a fascinating scene, not just for the way it propels the story forward, but for the way it bends our brains in the process. “We wanted more and more stylistic juxtaposition,” creator Dan Erickson explained to Vulture, “Something that seems really, really nice and beautiful next to something that’s horrifying and scary.” The way Mr. Milchick dances so flawlessly with each innie, none of whom seem to know what they are doing and subsequently dance like children, is a revelation. Mr. Milchick’s fixed, company man grin—one we’ve come to know and distrust on the show—only makes the sequences more compelling.

There seems to be a fascinating correlation between dance and violence in science fiction and horror. The first time I saw the Defiant Jazz scene (which is notably not the only weird dance sequence during the first season of Severance, though it is the most iconic), I was immediately reminded of the 2014 sci-fi film Ex Machina. The movie features a completely unhinged dance interlude in which Blue Book CEO Nathan (Oscar Isaac) avoids critical questions from his employee by performing a highly synchronized routine in an unbuttoned shirt under disco lights with his dance partner, who is of course a robot that he designed himself. Like the dance number in Severance, everything about this event is jarring—with tension and dread lying just beneath the surface. The musical selection provides a stark contrast to what is about to transpire. The sequence holds you by the throat and the longer it goes on, the more that grip tightens.

The Danse Macabre—the tradition of using dance as allegory for life and death—can be traced back to the 1400s. It has been used as a trope in art, music, and literature across centuries. In 1875, French composer Camille Saint-Saëns produced a “symphonic poem” titled Danse Macabre, in which death draws the dead out from their graves to dance for his fiddle. Saint-Saëns piece was adapted into an experimental eight-minute film directed by Dudley Murphy and developed by ballet dancer Adolph Bolm in 1922. In this work, the relationship between dance as an expression of the sinister is evident—it does not come as a surprise or shock to the audience. This remains true for many horror-coded dance sequences throughout the 20th century, but in these more recent examples I’ve been so fascinated by, dance isn’t used simply as a metaphor. It is utilized as a way to shock, disorient, and build tension—to bring the human body into focus in broad and creatively divergent ways.

Once you start looking for mystifying and unnerving dance sequences in genre film and television, they start to feel like they’re everywhere. Recent horror hits of the 21st century such as Black Swan (2010), Us (2019), Midsommar (2019), M3GAN (2022), Abigail (2024), and Apartment 7A (2024) all use dance in unique and startling ways that lend themselves to the horror elements in play while at the same time providing a dynamic contrast, breaking expectations. You can find early inklings of this shift from metaphor to disruptive spectacle in the late 20th century: Take a look at Angela’s ethereal, hellish dance in Night of the Demons (1988) or the 1977 Dario Argento classic Suspiria (set at a ballet academy), which was remade for American audiences in 2018.

While dance is a prominent component of the plot in some of these films, it’s unexpected and meant to jar the audience in the others. Ex-Machina writer/director Alex Garland told IndieWire that he wanted “to do something that just busts up the tone and woke people up” with the disco scene and he succeeds in doing just that. Sequences such as this one transfix—they stun and startle, both in the realm of the narrative and for the audience witnessing it as entertainment.

Perhaps my favorite use of dance in recent genre work, not including the “Defiant Jazz” scene in Severance, occurs during the final moments of Apartment 7A, the recent prequel to Rosemary’s Baby (1968). The film follows a young dancer who comes to live in the devil-worshiping Bramford apartment complex months before Rosemary does in the original story. Terry Gionoffrio (Julia Garner) is a driven, talented dancer struggling after a serious onstage accident that left her unable to perform the way she once had. She is lured into the Bramford by an older couple, the Castevets, who claim that they want to help her get back on her feet. As frightening dreams begin to take hold of Terry, she finds that her injured ankle is improving. Unfortunately, Terry’s miraculous recovery comes at a cost—one that fans of Rosemary’s Baby know too well: she is pregnant with the devil’s child.

At the end of the film, Terry seemingly agrees to join her devil-worshipping neighbors, declaring “Hail Satan!” before dancing around the room barefoot in a bloodstained shirt to “Be My Baby” by The Ronettes. Her audience in the room watches with rapt attention, as do we as the film’s viewers. “You were right, Minnie,” she says with a smile to Mrs. Castevet (Dianne Wiest). “It’s the role of a lifetime.” The scene is playful and rebellious, walking the line between calculated and carefree. Everyone is too busy watching to ask why Terry is dancing or what she is thinking. They assume she is now one of them. Until Terry suddenly leaps across the room and sits on the windowsill, a new grin on her face. Mrs. Castevet realizes what is happening just as it is too late. Terry throws herself backwards out the window, plummeting to her death. She cannot be controlled. She will not be controlled. No matter what it takes. “For me, the scene was so much about a coming back to self,” director and co-writer Natalie Erika James told Indiewire. “It is kind of triumphant in a way. It’s mournful but also very defiant.”

The runtime for the climax of Apartment 7A is roughly half the length of the “Defiant Jazz” sequence in Severance. The two dance scenes could not be more different in tone, style, even color palette—and yet both are completely captivating in their own ways. At the end of both scenes, a decision has been made. For Severance, Helly and her coworkers rally around Dylan against Mr. Milchick—deepening their bond as innies. In Apartment 7A, Terry chooses her own fate, giving one last unforgettable performance on her way out.

Perhaps this is the throughline when it comes to dance in 21st century genre media. In the examples above, it isn’t just about life and death—metaphor or spectacle. It is about choices, those made and those not. They reveal so much about the characters involved in them, from Mr. Milchick’s calculated charisma to Nathan’s self-indulgent megalomania to the lengths Terry is willing to go to hold on to her sense of self. Dance functions as a conduit for big moments, making sure the audience is truly paying attention right before turning the narrative on its head.

About forty minutes into the season two finale of Severance, we get yet another chance to experience the revelatory power of dance when Mr. Milchick launches another office celebration by introducing the members of a hitherto unknown department, “Choreography and Merriment.” The colored lights from “Defiant Jazz” return and a marching band floods the room, playing an aggressively upbeat version of the “Kier Anthem” (a tribute to the founder of Lumon). At the helm is a white-gloved Mr. Milchick, precisely orchestrating the whole performance. The camera cuts from character to character as the tempo builds, with our knowledge of each person’s storyline and internal turmoil ramping up the stakes. As the band begins a second song, Mr. Milchick dances alongside the band with a staff, forcing the audience as well as Mark S. (Adam Scott) and Helly to bear witness to the absolute absurdity that is this company’s corporate culture. Here, Severance turns dance into a kind of prison. Mark has to escape the room in order to save his outie’s wife, Gemma (Dichen Lachman), but the band is everywhere, blocking his every means of escape. Dance becomes an obstacle, forcing the characters to take action.

As a distraction, Helly steals Mr. Milchick’s walkie-talkie and runs away with it. The band continues to play, but Mr. Milchick must stop to follow her, affording Mark time to slip away. Helly locks Mr. Milchick in the bathroom, and Mark runs down the hall in search of Gemma. As in “Defiant Jazz,” this musical scene offers an opportunity to explore the bonds between these characters—to see what kind of choices they make when faced with impossible circumstances. “That marching band sequence really embodies, for me, the juxtaposition of the show,” Lower told Entertainment Weekly, “like this corporate world with this fully established band that they have at the ready. There’s something so wonderfully surreal about that. And at the same time, these characters are on this very human journey inside of this surreal moment.”

“Surreal” is a word often associated with these horror and sci-fi dance sequences, and with good reason. Reality and fantasy blur—at times forcing both the characters and the audience to question what is happening. It is because of this surreal quality that the function of dance is so malleable in these genres, adapting as needed to fit different plot structures. But whether you’re talking about Severance, Ex-Machina, Apartment 7A, or another of the many dance-infused genre works, one thing remains the same: the dances they bring us are visceral and unforgettable. They stick in our minds long after we’ve watched them. They are what we can’t wait to talk about afterwards—what we search online to rewatch and study. They reverberate in our memories as moments of awe. Disgust. Disbelief. Of course I felt the need to sit down and write about them…

So, what do you think of these scenes? Which horror or sci-fi dances haunt your dreams? Let us know in the comments…