This article is adapted from the September 28, 2024, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

Growing up in suburban New England, fluffernutters—two slices of white bread slathered with peanut-butter and marshmallow goop—were a lunchbox staple for many of my classmates. For the elementary school set, it’s a pretty optimal snack, one that fully dispenses with the vague pretense of fruit in a PB&J in favor of a maximum sugar rush.

The combination has been a cult fixture in the northeast for more than a century. We know it’s not good per se, but it holds a place of perverse regional pride that only comes from nostalgia. In 2006, when Massachusetts Senator Jarret Barrios proposed legislation that would forbid schools from serving fluffernutters more than once a week, it caused such a public uproar that Democratic Representative Kathi-Anne Reinstein declared, “I’m going to fight to the death for Fluff.”

Although Reinstein’s bill to make the fluffernutter the official state sandwich of Massachusetts remains in legal limbo, the word “fluffernutter” has since been added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. There’s also a Fluffernutter Day (on October 8th) as well as an annual What the Fluff? festival held in Somerville, Massachusetts, with events including “fluff jousting” and “fluff hairdo” (it’s exactly as messy as it sounds).

As a kid, I just assumed some other pre-teen had come up with the ingenious idea of smuggling dessert to school in sandwich form. But in reality, the fluffernutter began as a marketing ploy.

Emma Curtis, who co-founded the Curtis Marshmallow Company with her brother, first created a recipe for “Liberty Sandwiches” made with peanut butter and their trademarked Snowflake Marshmallow Creme in 1918. The creme was essentially the same as marshmallows, but minus the gelatin needed for the amorphous mass of corn syrup and egg whites to hold a solid shape.

Curtis may have come up with the sandwich, but credit for its key ingredient belongs elsewhere. Joseph Archibald Query, a Canadian living in Somerville, Massachusetts, invented Marshmallow Fluff the year prior, only to sell it in 1920 to the Durkee-Mower candy company when wartime sugar rationing made it too tough to make a profit.

Durkee-Mower tried all sorts of tactics to promote Marshmallow Fluff, including a 1930s radio show with dancing girls called the Flufferettes. Then when the 1960s rolled around, a branding agency helped them come up with the term “fluffernutter.” Thanks to a nationwide ad campaign, the name and the sandwich stuck.

And that’s hardly the only beloved American food tradition born out of marketing. “Modern American culture is just essentially a product of advertising,” says Christina Ward, author of American Advertising Cookbooks: How Corporations Taught Us to Love Bananas, Spam, and Jell-O.

Even most of the Norman Rockwell-esque Thanksgiving spread was born in American test kitchens belonging to General Mills (the faceless entity behind Betty Crocker), Campbell’s, and other corporations. In the early 20th century through the post-war years, Madison Avenue and the increasingly large food conglomerates it repped reshaped the ways in which Americans ate. Here are just a few of the foods and holiday traditions that resulted from that partnership.

Peanut Butter and Mayonnaise Sandwiches

If a fluffernutter strikes you as pedestrian, try this Depression-era PB&M. Cheap and calorically dense, the unlikely combo was probably born out of real desperation, but it was later seized on by Best Foods, which in the 1950s acquired both Hellmann’s mayonnaise and Skippy peanut butter. A 1963 ad read, “Skippy and Hellmann’s … together tremendous!”

“It came out of that time when all the food companies were amalgamated through all these mergers and acquisitions,” Ward says. “Their advertising, marketing departments, and development test kitchens were charged with, ‘Now we own five different food brands of different things—figure out a way that a consumer can use them all.’”

The post-war era saw the rise of the latchkey kid, who might hold down the fort while mom was at her ladies’ club or work. And a peanut butter and mayo sandwich was simple enough that a child could slap it together sans adult supervision after school. “Just conceptually, the whole idea of an after-school snack came out of advertising cookbooks,” Ward says. “And here’s a snack they can make for themselves.”

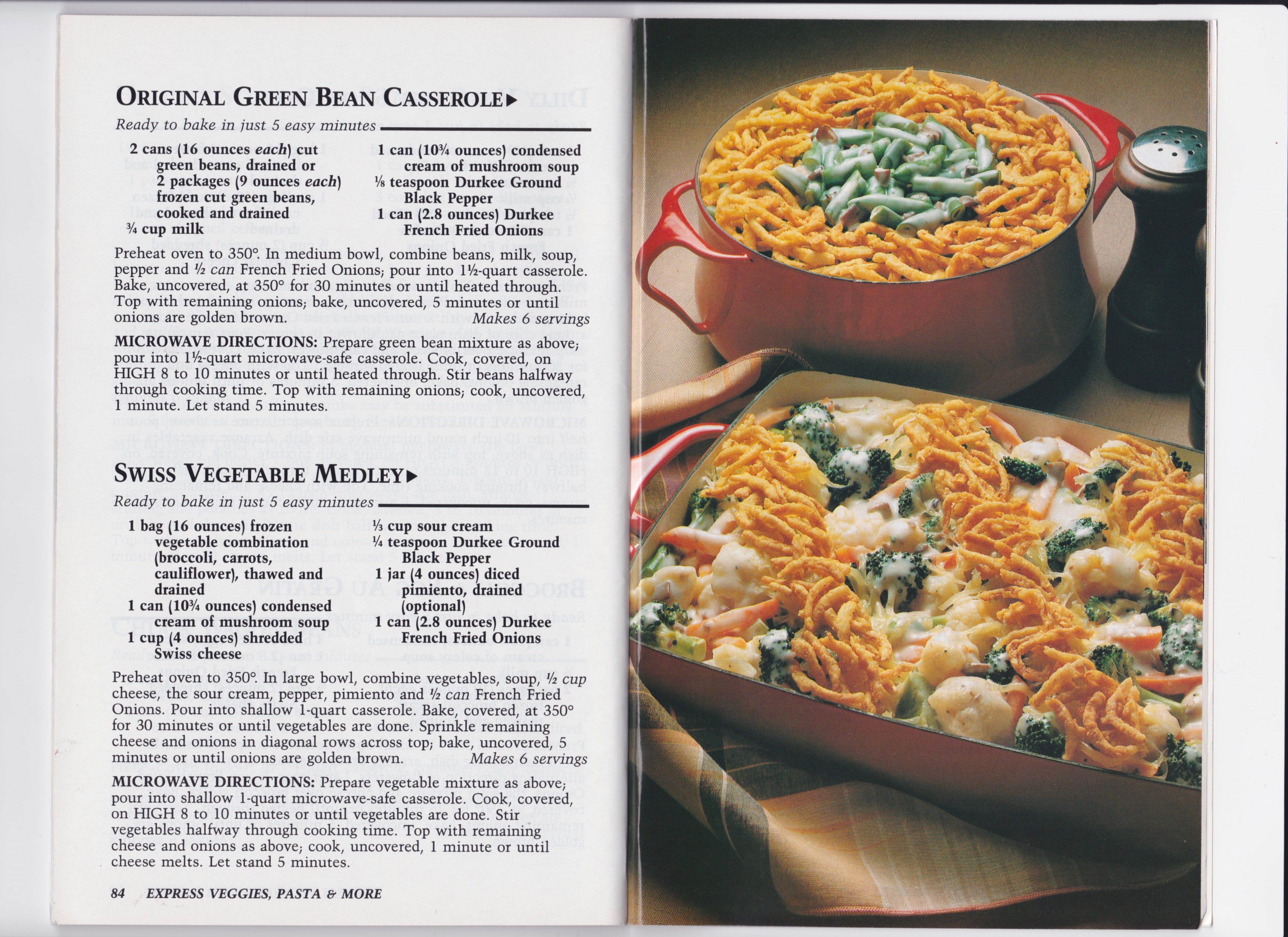

Green Bean Casserole

It’s not a coincidence that Campbell’s condensed soups started cropping up in recipes for everything from cakes to casseroles in the mid-20th century. The company distributed recipes claiming that harried housewives could make their lives easier by swapping a canned product for a homemade béchamel sauce.

Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup debuted in 1934 and quickly became the default base for tuna noodle casserole, turkey tetrazzini, and even Mormon-style funeral potatoes. Minnesota’s tater tot-loaded hotdish also incorporated cream of mushroom base, which earned the soup a nickname: “the Lutheran binder.”

But the one that really takes the cake is green bean casserole, composed of only six ingredients, three of which are canned Campbell’s products. In 1955, Dorcas Reilly invented the recipe for a “Green Bean Bake” in the company’s test kitchen and the rest is history.

“They marketed it specifically around Thanksgiving to try and tie it to holiday celebrations,” Ward says. “And sure enough, people did it.”

Lemon Pigs

In 2017, Anna Pallai, author of 70s Dinner Party: The Good, the Bad and the Downright Ugly of Retro Food convinced her Twitter followers to recreate lemon pigs from a 1971 book as a New Year charm for good luck. These portable porkers are the most foolproof of crafting projects.

Each lemon gets four toothpicks for legs, two cloves for eyes, and a curly aluminum foil tail. A penny protrudes from its mouth like an ancient Greco-Roman corpse prepared to cross the River Styx.

Recipes for lemon pigs, possibly a nod to German Glücksschwein (sugar pigs thought to bring good luck on New Year’s Eve) date back to the 19th century, but the recipe Pallai referenced was derived from 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from Alcoa—a cookbook by an aluminum foil company.

Gimmick or not, lemon pigs are something of a Gastro Obscura tradition. You can see our writer Andrew Coletti demonstrating how to make one here.

Pineapple Upside Down Cake

Ever wonder why 1950s American suburbanites suddenly got so excited about throwing torch-lit, Hawaiian-themed bashes in the backyard? “Dole is specifically responsible for creating this notion of summer picnic luaus for everybody,” Ward says.

In 1922, Dole Food Company bought the Hawaiian island of Lānaʻi and converted 20,000 acres into pineapple plantations, giving them a near monopoly on the fruit in the United States.

That meant the company had serious incentive to push pineapples everywhere, from Dole Whip, the iconic soft-serve sold at Disney theme parks, to all sorts of recipes designed to turn a backyard in Illinois into a pan-Polynesian tiki fantasy for an evening. “That idea that every place can be Hawai’i for a party came directly from [Dole],” Ward says.

Along with that came the idea that canned pineapple could add an exotic flair to literally any dish. In 1925, Dole held a competition for recipes using their product and pineapple upside down cake took the top prize.

Inverted, skillet-baked butter cakes with fruit had been around since the late 19th century, but this maraschino-crowned confection took the country by storm—thanks to an aggressive promotional push, of course.

German Christmas Pickles

It was only after I moved back to the United States from Berlin that I heard about a Weihnachtsgurke, or the “Christmas pickle.” Fashioned in the shape of a fat kosher dill, these ornaments can be found hanging on Christmas trees in Michigan and pockets of the Midwest. Allegedly, they’re a tradition brought over by German immigrants and whoever finds the lucky pickle bags an extra present.

Confused, I asked a handful of Germans about tree pickles, and they hadn’t heard of them either. According to legend, a Bavarian soldier fighting in the American Civil War requested a pickle on his deathbed and it magically cured him. An alternate tale claims that the people of Spreewald, a town outside Berlin known for its prolific pickle production, brought the concept over.

If both explanations sound suspiciously hokey, that’s probably because Woolworths most likely invented this quirky “ethnic” tradition in the 1800s to sling holiday kitsch. Perhaps my favorite element of the pickle tale is that word has gotten back to Germany, where a number of bemused publications have pondered the dubious origins of the tradition.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.