[ad_1]

My mother, Stephanie, doesn’t remember much about when she found the mysterious letters. The year was 1975, she was 10, and her father had just purchased a dilapidated two-story house on the Floridian island of Key West. Framed by two large Canary Island date palm trees that are still there to this day, the house at 616 Caroline Street was a mess, to say the least.

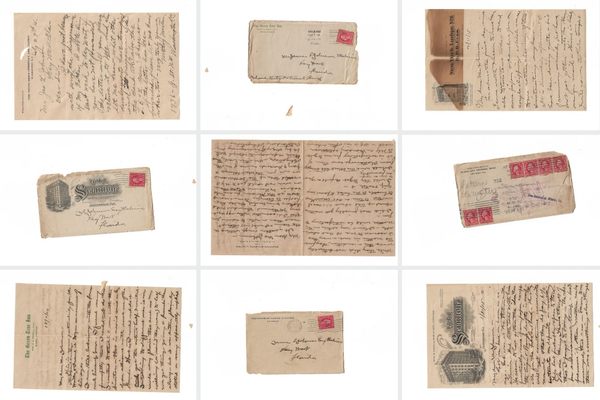

The day they moved in, Stephanie and her family were sifting through dirt, dust, and broken furniture when they came across the attic. She remembers finding a handful of antique dolls strewn around the area and a box containing 20 or so handwritten letters that were dated between 1913 and 1915.

She was too young to decipher the messy cursive scrawl, so the letters were packed away by my grandfather and slipped from my mother’s memory as she grew up. The family sold the house on Caroline Street, and Stephanie eventually moved to Italy.

As an adult shuffling through my grandfather’s belongings one day in 2019, 13 years after his death, she came across her childhood discovery tucked away in a plastic bag in a cardboard box. It had been over 40 years since she’d seen the letters, so she packed them up and took them back to Italy with her. “They were a part of my memories of being there as a little girl, and I knew they were going to be of some historical significance,” she says. Still unable to fully decipher them, she eventually passed the letters to me.

The collection of faded letters chronicles the correspondence between two bank colleagues: James L. Johnson, a cashier who lived at 616 Caroline Street, according to census data, and E. M. Martin, the bank’s vice president and a shadowy figure whose life was riddled with many peculiar twists and turns. Both men worked at the Island City National Bank, a small bank open for only 10 years.

In July 1915, Martin disappeared and the bank abruptly shuttered mere weeks later under suspicious circumstances.

Key West’s Island City National Bank has long been an enigma. Its bizarre story stretches over a decade between various cities, countries, and continents. And these hidden letters turned out to be a missing piece of the puzzle. The yellowed papers string together a winding tale of fraud, manhunts, amnesia, and many raised eyebrows.

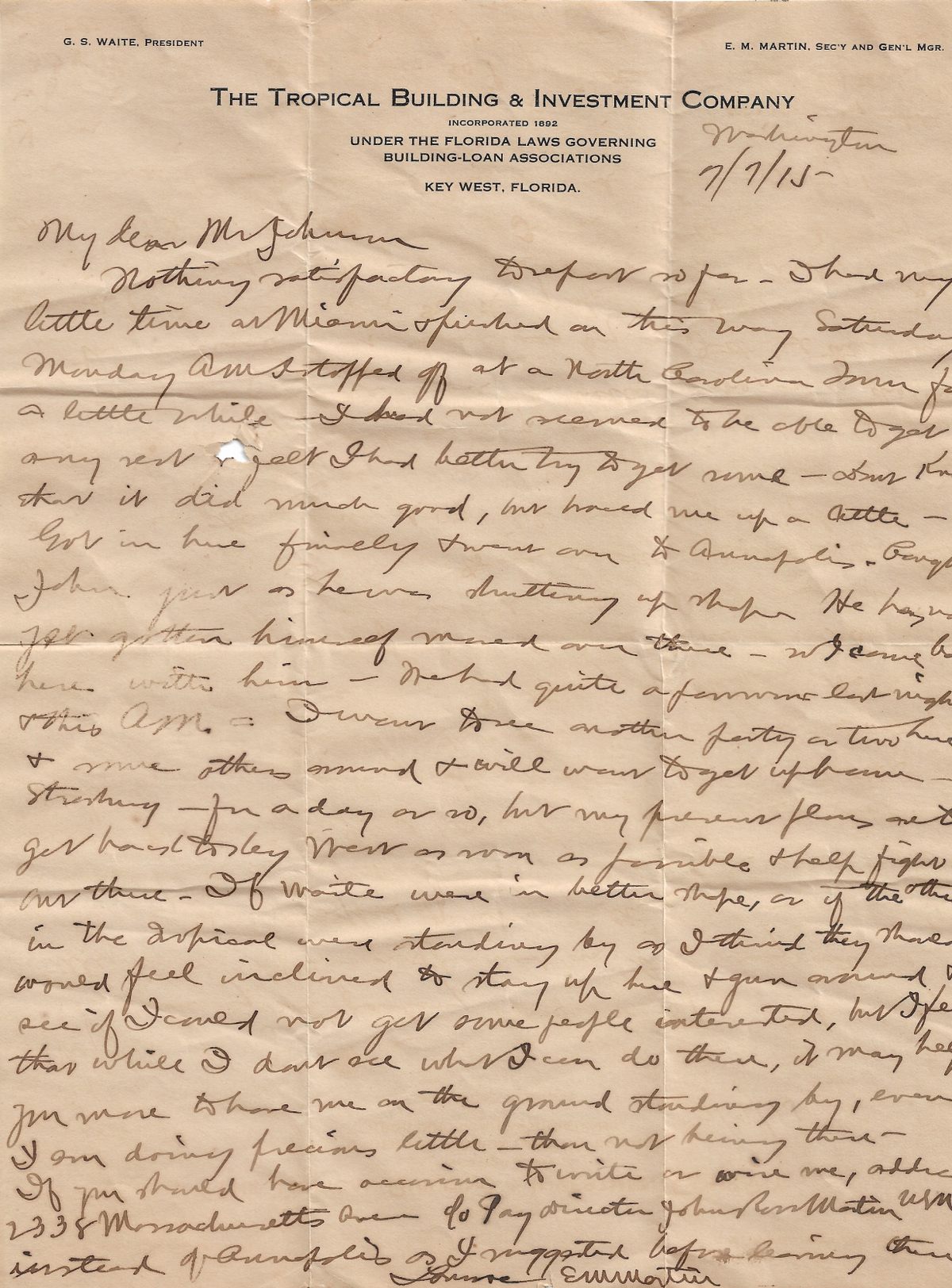

Martin was a 30-something-year-old physician hailing from a prominent family in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He arrived in Key West in the early 1890s, completely alone. Martin began working for the Tropical Investment Company, a real estate and loan association, as the secretary and general manager.

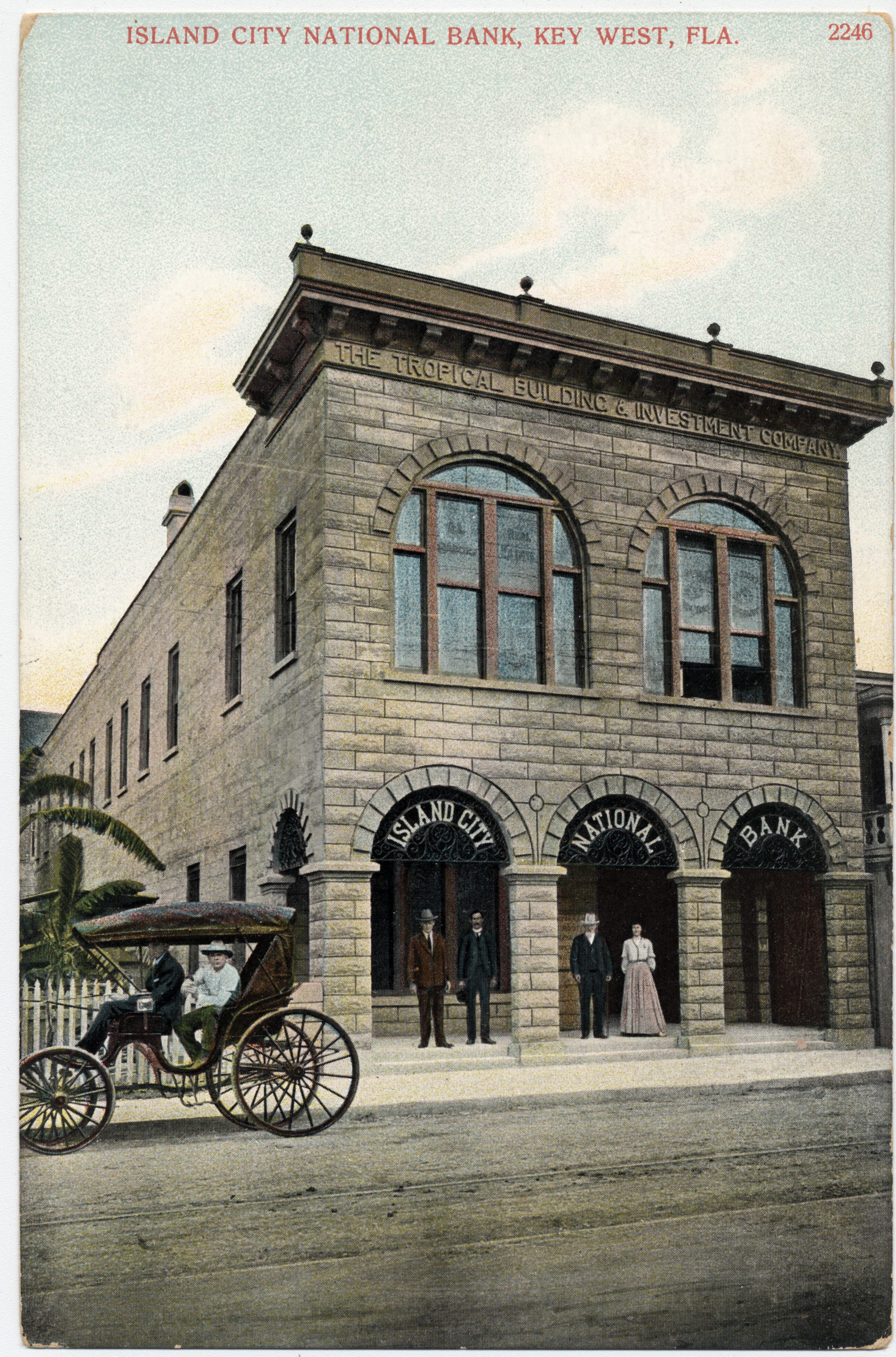

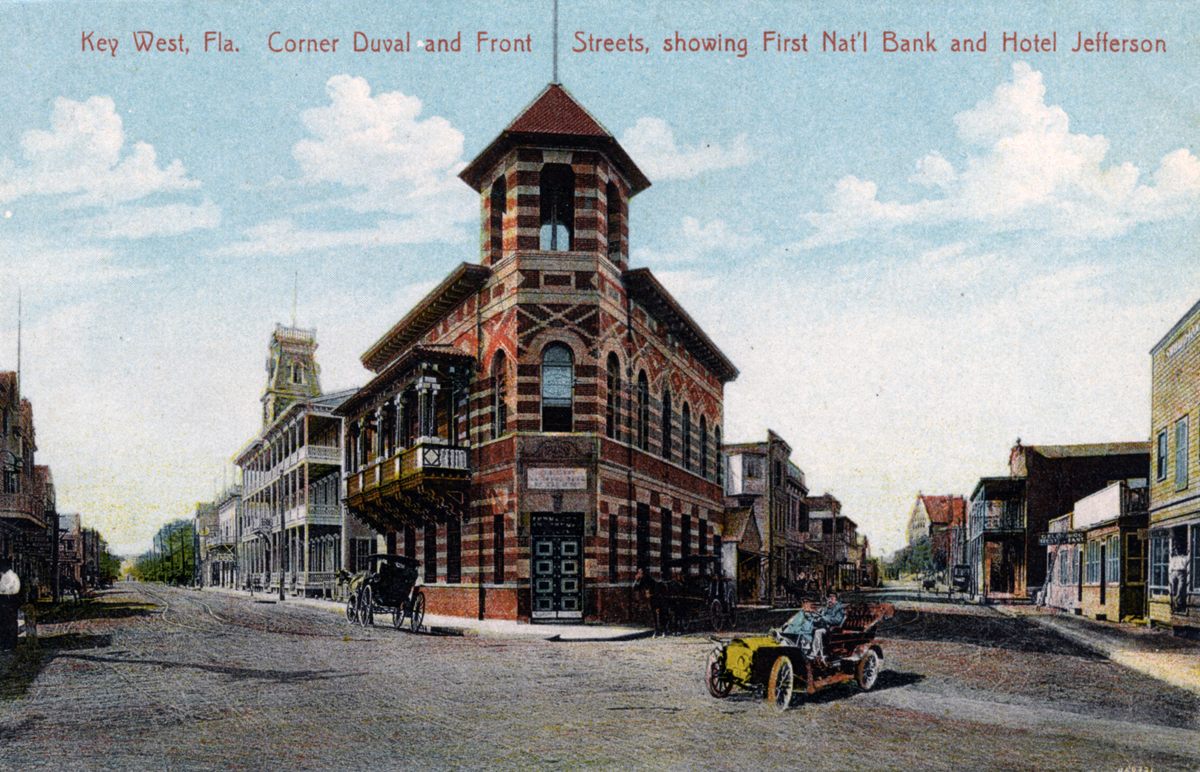

When the Island City National Bank opened on October 16, 1905, the new president (who also founded the Tropical Investment Company) hired Martin as the VP. Opening with a $100,000 capital in a two-floor brick building that still stands today, it made headlines for being the southernmost national bank in the United States.

The Island City National Bank appeared to fare well during the first nine years of operation, until trouble began rearing its head sometime in 1914. Martin started writing letters to Johnson from Miami, New York, and Washington, D.C., where he sought investors and loans, trying to keep the Island City National Bank afloat. By the time the bank shuttered in 1915, it had been carrying substantial loans from at least one trust company and three banks.

Banks at the time were not well regulated and they didn’t back their bills with government currency, explains Angela Zombek, a historian at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. As a result, many of these financial institutions would spring up and shut down quickly, an issue that wasn’t resolved until the Federal Reserve system was created in 1913. But in many ways, the bank’s financial troubles mirrored those afflicting the island itself.

By the end of the Civil War, Key West was “one of the most populated cities in Florida,” says Zombek, prosperous mainly thanks to a monopoly over the sponge trade. But by the time Island City National Bank opened, that industry was drying out as demand was being sourced outside the island.

Steamships also dropped Key West as a port of call in the late 1890s, effectively isolating the island and causing its economy to flatline. It never fully recovered over the rest of the century, especially once the Great Depression rolled around in 1929. This economic pitfall likely explains why Martin was soliciting external investors in other cities, explains Zombek.

By the beginning of 1915, the situation was dire. Martin had been spending less time in Key West, and his letters to Johnson became increasingly negative, occasionally punctuated with vague references to “interested parties” or “indefinite inquiries.” In the months leading up to the bank’s closure, Martin was receiving letters from banks threatening to drop their loans. By July 1915, he had left the island, claiming to seek investors in Miami and Washington D.C.

Martin’s last letter to Johnson was written on July 7 from his brother’s home in D.C. He disappeared the day after, much to the dismay of his brother, John, and sister, Agnes. Agnes wrote him a four-page letter, begging him to “let go now if you truly see that you are truly getting in deeper and deeper.” How the letter came to be in Johnson’s care is unknown.

Roughly two weeks later, on July 23, the bank shuttered for good, citing an unusual amount of withdrawals, which had depleted its cash reserves. News of Martin’s disappearance broke days later, prompting a man claiming to be Martin’s son to write a letter to Johnson inquiring after his missing father.

Months later, other banks began calling in their loans. The First National Bank of Miami, for example, charged Martin $3,182.66 for an indebted loan, roughly $97,000 today.

The bank’s spectacular and rather rapid fall from grace turned out to be Martin’s doing. He had been siphoning money from the Island City National Bank and funneling it into the floundering Tropical Investment Company, an action that was so destructive for the bank’s investors that it spurred a two-year global manhunt for the missing man. It wasn’t until 1917 that the Secret Service discovered Martin halfway across the world, in Australia, according to clippings from The Tampa Tribune.

There’s a gap in Martin’s story here, but the details become stranger. “It’s a story with outrageous twists and turns,” says Corey Malcom, the lead historian at the Florida Keys History Center at the Key West Library. “It involves Martin taking off when he saw everything was collapsing, winding up in Australia, but then up in Oklahoma City—living his life as another person.” Though it’s unclear what happened in Australia, when Martin arrived in Oklahoma City, he started a new life under a new name: John Porter Williams.

According to a profile published by the Commercial Appeal in November 1925, Martin apparently suffered from amnesia and had no recollection of his life prior to July 11, 1915, by which point he already believed his name to be Williams. The article describes him as a quiet, guarded man with a white beard who made few friends and “lived silent and a little apart from the main stream of city life.” Pieces of his memory began coming back to him in short bursts in 1921, like the names John and Agnes.

In a 1921 letter to an acquaintance, Martin writes of his fragmented memory: “Sometimes I have the feeling that this experience (whatever it is) that I am going through has happened before. And what is more satisfactory, a feeling that it may happen again.” There was no way to know it at the time, but these two sentences would prove to be the smoking gun in unraveling Martin’s life story.

In 1924, a year after Martin became the head of the prosperous Mutual Savings and Loan Association, he began inquiring after John and Agnes. He had his lawyer publish a photo of himself in various papers, which eventually drew the notice of one of his cousins. She, in turn, informed Agnes that her long-lost brother was not only alive, but had no memory of her. Agnes, who still lived at the family home in Pennsylvania, and Martin reunited that year and spent Christmas together.

The newspaper profile also revealed that Martin had been married—and had gone through amnesia before. In the late 1880s, he and his wife and young son lived together in Tennessee, where his marriage was apparently so miserable that it supposedly triggered a mental breakdown. Martin disappeared from the family home for a year, at which point he claimed he lost all memory of his life and believed his name to be none other than Williams. Upon regaining his memory and returning to his family, his wife divorced him, and Martin began his life anew in Key West.

The parallels between the two bouts of amnesia are uncanny: twice, they appear to happen in moments of acute psychological distress; twice he begins anew as a figure in the banking world; and twice during his memory loss he believes his name to be Williams. Was the name John Porter Williams an alter ego Martin could adopt to start his life over during particularly unhappy moments, or was it legitimate amnesia, a drastic survival method employed by his psyche to protect him during moments of severe stress? It’s a question only Martin himself can answer. One thing is certain: The bouts of amnesia irrevocably shaped the trajectory of Martin’s life and those around him.

When Martin died of natural causes in September 1925, his body was sent back to “the house in which he was born and grew to manhood, and his sister who for more than 10 years awaited his return, with confidence that would come again, is comforted in the thought that he is to sleep by the side of his own loved ones,” according to a letter written by the cousin who identified him the year before.

While the history of the Island City National Bank has been somewhat lifted from obscurity, questions still remain. What was Martin doing in Australia for two years? Why was he not held accountable when discovered? Why did Johnson hold on to his letters for 45 years? We may never know the answers, but the Island City National Bank is a reminder that sometimes the most colorful stories lie in wait in the most seemingly benign things: an old building, newspaper clippings, or a stack of dusty letters discovered by a little girl.

[ad_2]

Source link